This article explores the elegance and timeless appeal of gold pearl necklaces, detailing their history, styles, care, and how to choose the perfect piece for any occasion. Gold pearl necklaces are not just accessories; they are statements of sophistication and grace that have captivated jewelry lovers for generations.

The History of Gold Pearl Necklaces

The rich history of gold pearl necklaces dates back centuries, intertwining with various cultures and fashion trends that highlight their enduring allure and significance in jewelry. Historically, pearls were deemed precious and often associated with royalty. Ancient civilizations, such as the Egyptians and Romans, adorned themselves with pearl jewelry, believing it brought them luck and prosperity. Over the years, the combination of gold and pearls has evolved, but their charm remains unaltered, symbolizing elegance and wealth.

Types of Gold Pearl Necklaces

Understanding the different types of gold pearl necklaces available can help you make informed choices, whether you’re looking for a classic strand or a more contemporary design. Here are some popular styles:

- Classic Strand Necklaces: These timeless pieces feature a simple arrangement of pearls, often strung together with gold accents for added elegance and sophistication.

- Single vs. Multi-Strand Designs: Single-strand designs offer a minimalist aesthetic, while multi-strand options add depth and texture, making them suitable for both casual and formal occasions.

- Customized Designs: Customized gold pearl necklaces allow for personalization, enabling wearers to select specific pearl types, sizes, and gold settings that reflect their individual style.

- Contemporary Styles: Contemporary styles of gold pearl necklaces incorporate modern design elements, often blending pearls with other materials to create unique and striking pieces.

Choosing the Right Gold Pearl Necklace

Selecting the perfect gold pearl necklace involves considering various factors, including personal style, occasion, and the types of pearls and gold used in the piece. Start by understanding your personal style, as it ensures that the piece complements your wardrobe and enhances your overall look. Different occasions call for different necklace styles; therefore, selecting a versatile piece that can transition from day to night is often a wise choice.

Care and Maintenance of Gold Pearl Necklaces

Proper care and maintenance of gold pearl necklaces are essential to preserve their beauty and longevity, ensuring they remain cherished pieces in your jewelry collection. Regular cleaning using gentle methods can help maintain the luster of gold pearl necklaces, preventing the buildup of dirt and oils that can dull their appearance. Storing gold pearl necklaces correctly is vital; using soft pouches or dedicated jewelry boxes can prevent scratches and tangling, ensuring they stay in pristine condition.

Popular Trends in Gold Pearl Necklaces

Staying updated on popular trends in gold pearl necklaces can help you choose pieces that are not only timeless but also fashionable and in line with current styles. Layering gold pearl necklaces with other types of jewelry has become a popular trend, allowing for creative combinations that showcase personal style and make a bold statement. Additionally, mixing pearls with other materials, such as gemstones or metals, is a trend that adds texture and uniqueness to gold pearl necklaces, appealing to modern fashion sensibilities.

The Symbolism of Pearls in Jewelry

Pearls have long been associated with various meanings and symbolism in jewelry, adding depth to the significance of gold pearl necklaces beyond their aesthetic appeal. Often regarded as symbols of purity and wisdom, pearls enhance the emotional value of gold pearl necklaces, making them meaningful gifts for special occasions. In many cultures, pearls represent love and loyalty, making gold pearl necklaces ideal for commemorating significant relationships and milestones in life.

Where to Buy Gold Pearl Necklaces

Finding the right retailer for gold pearl necklaces is essential for ensuring quality and authenticity, whether you prefer shopping online or in physical stores. Both online retailers and local jewelers offer unique advantages; online shopping provides convenience, while local jewelers offer personalized service and the opportunity to see pieces in person. When purchasing a gold pearl necklace, it’s important to look for quality certifications, return policies, and customer reviews to ensure a satisfying buying experience.

The History of Gold Pearl Necklaces

is a captivating journey that traverses centuries, revealing the intricate relationship between these exquisite pieces of jewelry and various cultures around the globe. Gold pearl necklaces have not only adorned the necks of royalty and the elite but have also been embraced by individuals across different social strata, symbolizing wealth, beauty, and status.

Dating back to ancient civilizations, pearls have been valued for their rarity and beauty. The earliest records of pearl jewelry can be traced to the Roman Empire, where pearls were considered a luxury item. They were often worn by the upper class and were associated with the divine, believed to bring protection and prosperity. The Romans even went so far as to create laws regulating the wearing of pearls, ensuring that only the wealthy could enjoy their beauty.

In Asia, particularly in China, pearls have held significant cultural importance for thousands of years. They were believed to symbolize purity and were often used in traditional bridal jewelry. The use of pearls in Chinese culture reflects a deep appreciation for nature and the belief in the spiritual properties of gemstones. This reverence for pearls has continued into modern times, making them a staple in Asian bridal attire.

During the Renaissance, gold pearl necklaces became a popular fashion statement among the European elite. The combination of gold and pearls represented a harmonious blend of luxury and elegance. Artists and jewelers began to experiment with intricate designs, incorporating gold filigree and elaborate settings that showcased the pearls’ natural beauty. This period marked a significant evolution in jewelry design, setting the stage for contemporary styles.

The 20th century saw a resurgence of interest in gold pearl necklaces, particularly during the 1920s and 1950s. Iconic figures such as Audrey Hepburn and Grace Kelly popularized the classic strand of pearls, associating them with timeless elegance and sophistication. The simplicity of a gold pearl necklace became synonymous with refined taste, making it a must-have accessory for women of all ages.

Today, the history of gold pearl necklaces is celebrated through various styles and designs that pay homage to their rich heritage. From traditional strands to modern interpretations that incorporate contemporary materials, these necklaces continue to captivate jewelry lovers worldwide. The enduring allure of gold pearl necklaces lies not only in their aesthetic appeal but also in the stories they carry, connecting generations through a shared appreciation for beauty and craftsmanship.

Types of Gold Pearl Necklaces

Understanding the variety of gold pearl necklaces available is essential for making informed choices that reflect your style and needs. These necklaces not only embody elegance but also offer versatility for different occasions. Here, we delve into the different types of gold pearl necklaces, ensuring you find the perfect piece to enhance your jewelry collection.

- Classic Strand Necklaces

- Single-Strand Necklaces: These are the quintessential gold pearl necklaces, featuring a single line of pearls elegantly strung together. They are perfect for both casual and formal settings, providing a timeless look that never goes out of style.

- Multi-Strand Necklaces: For those looking to make a statement, multi-strand designs offer a more dramatic and textured appearance. They can be layered for added depth, making them ideal for special occasions.

- Customized Designs

- Personalized Necklaces: Customized gold pearl necklaces allow you to select specific pearls, sizes, and gold settings. This personalization ensures that your necklace reflects your unique style and preferences, making it a cherished piece.

- Engraved Options: Some jewelers offer engraving services, allowing you to add a special date or name, enhancing the sentimental value of your necklace.

- Contemporary Styles

- Mixed Material Necklaces: Modern designs often blend pearls with other materials, such as gemstones or metals, creating striking and unique pieces. These necklaces appeal to fashion-forward individuals looking for something different.

- Geometric and Asymmetrical Designs: Contemporary styles may incorporate geometric shapes or asymmetrical arrangements, offering a fresh take on the traditional gold pearl necklace.

- Statement Necklaces

- Bold and Chunky Styles: These necklaces often feature larger pearls or elaborate designs that draw attention. They are perfect for making a fashion statement and can elevate even the simplest outfit.

- Layered Looks: Combining multiple gold pearl necklaces of varying lengths and styles can create a trendy layered effect, allowing for creative expression and versatility.

When choosing a gold pearl necklace, consider the occasion and your personal style. Whether you prefer the timeless elegance of a classic strand or the modern flair of a contemporary design, there is a gold pearl necklace to suit every taste and event. By understanding the different types available, you can select a piece that not only complements your wardrobe but also enhances your overall aesthetic.

Classic Strand Necklaces

are a quintessential element of timeless jewelry, embodying elegance and sophistication. These necklaces typically consist of a series of pearls, seamlessly strung together, often enhanced with gold accents that elevate their aesthetic appeal. The simplicity of the design allows for versatility, making them suitable for various occasions, from casual outings to formal events.

The charm of classic strand necklaces lies in their universal appeal. These pieces have been adored for centuries, often worn by icons of fashion and royalty alike. The combination of pearls and gold not only signifies luxury but also represents a rich heritage in jewelry-making. Pearls, known for their lustrous sheen, are often associated with purity and elegance, while gold accents add a touch of warmth and richness to the overall design.

Classic strand necklaces come in various designs, each offering a unique interpretation of this timeless style. The most common variations include:

- Single Strand: A simple yet elegant choice that highlights the beauty of each pearl.

- Multi-Strand: These designs feature multiple strands of pearls, creating a more dramatic effect and added texture.

- With Gold Accents: Incorporating gold beads or clasps provides a sophisticated contrast to the pearls, enhancing their visual appeal.

When selecting a classic strand necklace, the type of pearls plays a crucial role in determining the necklace’s overall look and feel. Here are some popular types of pearls to consider:

- Akoya Pearls: Known for their round shape and high luster, these pearls are a classic choice for strand necklaces.

- Freshwater Pearls: Available in various shapes and colors, they offer a more affordable option without compromising on beauty.

- South Sea Pearls: Renowned for their size and rarity, these pearls create a luxurious statement piece.

Styling a classic strand necklace can be both fun and rewarding. Here are some tips to make the most of this timeless piece:

- Layering: Pair your classic strand with other necklaces of varying lengths for a trendy layered look.

- Mixing Materials: Combine your pearl necklace with other materials, such as leather or gemstones, for a contemporary twist.

- Occasional Wear: Dress up a simple outfit for formal occasions or add elegance to casual wear by simply wearing the necklace alone.

To ensure the longevity of your classic strand necklace, proper care is essential. Here are some maintenance tips:

1. Clean your pearls regularly with a soft cloth to remove oils and dirt.2. Store your necklace in a soft pouch or lined jewelry box to prevent scratches.3. Avoid exposing your pearls to harsh chemicals or perfumes.

In conclusion, classic strand necklaces are more than just jewelry; they are a statement of elegance and sophistication that transcends time. Whether you are looking to invest in a piece for yourself or as a gift, understanding their history, design variations, and care can help you appreciate these timeless treasures even more.

Single vs. Multi-Strand Designs

When it comes to gold pearl necklaces, the choice between single-strand and multi-strand designs can significantly impact both the aesthetic and the versatility of the piece. These two styles cater to different tastes and occasions, making it essential to understand their unique characteristics and advantages.

Single-strand necklaces embody a minimalist aesthetic, offering a clean and elegant look that is perfect for those who appreciate simplicity. This design typically features a single line of pearls, often interspersed with gold accents or clasps that add a touch of sophistication. The understated nature of single-strand necklaces makes them suitable for everyday wear, allowing them to seamlessly complement both casual and formal outfits. Whether paired with a simple blouse or a chic evening gown, a single-strand necklace enhances the wearer’s elegance without overwhelming their ensemble.

On the other hand, multi-strand necklaces introduce a sense of depth and texture that can elevate any look. These designs consist of multiple strands of pearls, which can vary in length, thickness, and arrangement. The layered effect creates a more dynamic appearance, making multi-strand necklaces a popular choice for special occasions or events where one wishes to make a statement. The intricate design of multi-strand necklaces allows for creative combinations of colors and sizes, enabling wearers to express their individuality and style.

Moreover, the versatility of multi-strand designs cannot be overlooked. They can be styled in numerous ways, allowing for a range of looks from bohemian to classic elegance. For instance, a multi-strand pearl necklace can be worn as a choker for a vintage-inspired look or draped longer for a more contemporary vibe. This adaptability makes them suitable for various events, from weddings to cocktail parties.

In terms of maintenance, single-strand necklaces are generally easier to care for, as they are less prone to tangling compared to their multi-strand counterparts. However, multi-strand designs require careful handling to maintain their shape and prevent any damage to the strands. Regular cleaning and proper storage are essential for keeping both styles looking their best.

Ultimately, the choice between single and multi-strand designs comes down to personal preference and the intended use of the necklace. While single-strand necklaces provide a timeless and elegant option for daily wear, multi-strand necklaces offer a more dramatic and versatile choice for those looking to make a bold impression. Both styles hold their charm and can be treasured additions to any jewelry collection.

Customized Designs

in gold pearl necklaces represent a unique opportunity for individuals to express their personal style. These bespoke pieces allow wearers to select specific elements that resonate with their individuality, making each necklace a true reflection of the owner’s taste.

When considering a customized gold pearl necklace, one of the first aspects to think about is the type of pearls you want to incorporate. There are several varieties, including Akoya, Freshwater, South Sea, and Tahitian pearls, each offering distinct characteristics. Akoya pearls are known for their luster and round shape, making them a popular choice for classic designs. Freshwater pearls, on the other hand, are available in various shapes and colors, allowing for more creative freedom. South Sea and Tahitian pearls are larger and often more expensive, adding a luxurious touch to any necklace.

In addition to pearl selection, the size of the pearls plays a crucial role in the overall design. Larger pearls can create a bold statement, while smaller pearls often lend a delicate and understated elegance. Customization allows you to choose sizes that best suit your style and the occasions for which you intend to wear the necklace.

The gold setting is another vital component of a customized gold pearl necklace. Options range from yellow gold, white gold, and rose gold, each offering different aesthetic appeals. Yellow gold provides a classic look, while white gold offers a modern, sleek finish. Rose gold, with its warm hue, adds a romantic touch. Selecting the right gold type enhances the pearls’ beauty and complements your skin tone.

Furthermore, the necklace length can be tailored to your preference. Standard lengths include choker, princess, and matinee, each serving different styles and occasions. A choker sits snugly around the neck, making it perfect for formal events, while a princess length falls gracefully just below the collarbone, ideal for everyday wear. Customizing the length ensures that the necklace sits perfectly against your neckline, enhancing your overall appearance.

Another aspect of customization is the addition of personalized elements, such as engravings or charms. Many jewelers offer the option to engrave initials, dates, or meaningful symbols on the gold clasp or pendant. This personal touch not only adds sentimental value but also transforms the necklace into a cherished keepsake.

Moreover, the design style can be customized to reflect your unique taste. Whether you prefer a simple strand, a multi-strand arrangement, or a more intricate design featuring gold accents or other gemstones, the possibilities are nearly endless. Collaborating with a skilled jeweler can help you visualize your ideas and bring your dream necklace to life.

In conclusion, customized gold pearl necklaces offer a blend of luxury and personal expression. By selecting specific pearl types, sizes, gold settings, and design elements, wearers can create a one-of-a-kind piece that truly represents their individual style. This personalization not only enhances the aesthetic appeal of the necklace but also adds emotional significance, making it a perfect gift for oneself or a loved one.

Contemporary Styles

Contemporary Styles of Gold Pearl NecklacesIn the ever-evolving world of jewelry design, contemporary styles of gold pearl necklaces have emerged as a vibrant fusion of tradition and innovation. These modern pieces not only reflect the classic elegance of pearls but also embrace contemporary aesthetics, making them a popular choice among fashion-forward individuals. By incorporating unique design elements and blending pearls with various materials, contemporary gold pearl necklaces create striking statements that appeal to diverse tastes.

Today’s gold pearl necklaces often feature innovative designs that break away from traditional norms. Designers are increasingly experimenting with asymmetrical shapes, geometric patterns, and mixed materials. For instance, combining pearls with semi-precious stones, leather, or even acrylic elements adds a touch of modernity to these timeless pieces. This blending not only enhances the visual appeal but also allows for a broader range of styles, from bohemian to minimalist.

Another defining characteristic of contemporary gold pearl necklaces is the trend of layering. Many fashion enthusiasts opt to wear multiple necklaces of varying lengths and styles, creating a personalized look that showcases their unique style. This trend encourages individuals to mix and match different textures and materials, allowing for endless possibilities. Additionally, many jewelers now offer customization options, enabling customers to select specific pearl types, colors, and gold settings that resonate with their personal aesthetic.

Contemporary gold pearl necklaces are designed with versatility in mind, making them suitable for a variety of occasions. Whether you’re dressing up for a formal event or looking for a chic accessory for everyday wear, there’s a contemporary style that fits the bill. For instance, a delicate gold chain with a single pearl pendant can add a subtle touch of elegance to a casual outfit, while a bold multi-strand necklace with colorful gemstones can serve as a stunning statement piece for special occasions.

In a world where self-expression is paramount, contemporary gold pearl necklaces empower wearers to emphasize their individuality. The incorporation of unique design elements allows for personal storytelling through jewelry. For instance, a necklace that combines pearls with charms or meaningful symbols can hold sentimental value, making it not just an accessory but a cherished piece of art. This focus on individuality has made contemporary gold pearl necklaces a favorite among those who wish to stand out while still embracing a classic element.

In summary, contemporary styles of gold pearl necklaces represent a harmonious blend of luxury and modern design. By embracing innovative materials, layering trends, and personalization, these necklaces cater to the diverse tastes of today’s fashion enthusiasts. As the jewelry landscape continues to evolve, gold pearl necklaces remain a timeless choice that resonates with both tradition and contemporary flair.

Choosing the Right Gold Pearl Necklace

is an essential step in enhancing your jewelry collection. With a myriad of styles and options available, making an informed decision can elevate your personal style and ensure that you choose a piece that is not only beautiful but also meaningful. This guide will explore key factors to consider when selecting the ideal gold pearl necklace, including personal style, occasion, and the types of pearls and gold used in the piece.

Before diving into the world of gold pearl necklaces, it’s crucial to assess your personal style. Are you drawn to classic elegance, or do you prefer contemporary designs? Knowing your style will help you select a necklace that complements your wardrobe.

- Classic Styles: If your wardrobe consists of timeless pieces, a classic strand necklace may be the perfect addition. These often feature uniform pearls strung together, creating a sophisticated look.

- Modern Designs: For those who enjoy a more eclectic style, contemporary designs that mix pearls with other materials can provide a unique flair.

The occasion for which you are purchasing the necklace plays a significant role in your choice. Different events call for different styles of jewelry.

- Casual Events: A simple, understated gold pearl necklace can enhance your everyday look without overpowering your outfit.

- Formal Occasions: For weddings or galas, opt for more elaborate designs, such as multi-strand necklaces or those with intricate gold settings.

Understanding the different types of pearls and gold used in necklaces is vital for making an informed choice. Pearls come in various shapes, sizes, and colors, each adding a distinct character to the necklace.

- Freshwater Pearls: Known for their affordability and variety, these pearls are perfect for casual wear.

- Akoya Pearls: These are more classic and often used in traditional pearl necklaces, characterized by their high luster.

- Gold Options: Consider whether you prefer yellow, white, or rose gold, as the metal can significantly affect the overall appearance of the necklace.

When selecting a gold pearl necklace, quality and craftsmanship should not be overlooked. Inspect the necklace for any signs of wear and ensure that the pearls are securely attached. High-quality necklaces will have a smooth finish and a well-made clasp.

Establishing a budget before you start shopping can help narrow down your options. Gold pearl necklaces can range significantly in price based on the type of pearls, gold purity, and craftsmanship. Setting a budget allows you to focus on pieces that meet your financial criteria while still offering beauty and elegance.

Don’t hesitate to seek expert advice from jewelers. They can provide valuable insights into the best options based on your preferences and budget. Additionally, they can help you understand the differences in pearl quality and gold types, ensuring you make a well-informed decision.

In conclusion, choosing the right gold pearl necklace involves careful consideration of your personal style, the occasion, and the specifics of the pearls and gold used in the piece. By taking the time to assess these factors, you can find a stunning necklace that complements your unique style and enhances your collection.

Consider Your Personal Style

When it comes to selecting a gold pearl necklace, understanding your personal style is paramount. Your personal style reflects your individuality and can significantly influence how you feel about your overall appearance. A necklace that resonates with your unique taste not only enhances your wardrobe but also boosts your confidence.

Gold pearl necklaces come in various designs, from classic to contemporary, and each style can convey a different message about your personality. For instance, if you lean towards a minimalistic aesthetic, a simple single-strand gold pearl necklace may be the perfect choice. This style is versatile and can effortlessly transition from casual to formal settings, making it a staple in any jewelry collection.

On the other hand, if your style is more eclectic, you might prefer a multi-strand design or a necklace that incorporates vibrant gemstones alongside pearls. Such pieces often make a bold statement and can showcase your adventurous spirit. Understanding the type of jewelry that resonates with you will guide you in making an informed choice that aligns with your fashion sensibilities.

Additionally, consider the color palette of your wardrobe. If you frequently wear warm tones, a gold pearl necklace with creamy or golden pearls can beautifully complement your outfits. Conversely, if your wardrobe consists of cooler colors, opt for necklaces featuring white or silver-toned pearls. This attention to detail can enhance your overall look and ensure that your necklace harmonizes with your attire.

Another essential factor to consider is the occasion for which you are purchasing the necklace. Are you looking for something to wear daily, or do you need a statement piece for special events? Understanding the context in which you will wear your necklace can help narrow down your options. For instance, a delicate gold pearl necklace may be more suitable for everyday wear, while a more ornate design could be perfect for formal occasions.

Furthermore, don’t overlook the importance of comfort. Your personal style should not only reflect your aesthetic preferences but also your comfort level. If you prefer lightweight jewelry, choose a gold pearl necklace that is easy to wear for extended periods. This consideration ensures that you feel at ease while showcasing your stunning piece.

Ultimately, selecting a gold pearl necklace that aligns with your personal style involves a combination of aesthetics, color coordination, occasion, and comfort. By taking the time to understand your preferences and how they relate to the jewelry you choose, you can find a piece that not only enhances your look but also resonates with your identity. This thoughtful approach will ensure that your gold pearl necklace becomes a cherished part of your collection, reflecting your unique style for years to come.

Occasion and Versatility

When it comes to jewelry, the occasion plays a crucial role in determining the style and type of piece you choose. A gold pearl necklace is a perfect example of a versatile accessory that can effortlessly transition from day to night, making it an essential addition to any jewelry collection.

During the day, a gold pearl necklace can be worn in a more understated manner. Pairing it with a simple blouse or a tailored blazer creates a polished look suitable for the office or casual outings. The subtle elegance of pearls, combined with the warmth of gold, adds a touch of sophistication without being overly flashy. Opting for a single-strand design can enhance this minimalist aesthetic, allowing the natural beauty of the pearls to shine through.

As the day turns into night, the same necklace can be dressed up for more formal occasions. For instance, layering a multi-strand gold pearl necklace over a little black dress instantly elevates your ensemble, providing a statement piece that draws attention. Adding complementary earrings or a bracelet can further enhance the overall look, making you feel confident and glamorous. This adaptability makes gold pearl necklaces particularly appealing for events such as weddings, cocktail parties, or romantic dinners.

Moreover, the versatility of gold pearl necklaces is not limited to their styling options. They can also be customized to fit different occasions. Many jewelers offer personalized designs where you can choose the type and size of pearls, as well as the gold settings. This means you can create a unique piece that reflects your personal style while remaining appropriate for various events.

- Casual Events: A simple gold pearl necklace can complement everyday outfits, such as jeans and a t-shirt, adding a touch of elegance without being overbearing.

- Business Attire: Pairing a classic strand gold pearl necklace with a tailored suit can enhance professionalism while maintaining a chic appearance.

- Formal Occasions: Multi-strand designs or those embellished with additional gemstones can transform your look for evening events, making them ideal for weddings or galas.

In conclusion, the ability of a gold pearl necklace to transition seamlessly between different settings and styles makes it a wise investment for anyone looking to enhance their jewelry collection. Whether you’re dressing for work, a casual day out, or an elegant evening affair, a gold pearl necklace can be your go-to accessory that embodies both luxury and timelessness.

Care and Maintenance of Gold Pearl Necklaces

Proper care and maintenance of gold pearl necklaces are essential to preserve their beauty and longevity, ensuring they remain cherished pieces in your jewelry collection. Gold pearl necklaces combine the luxurious allure of gold with the timeless elegance of pearls, making them a favorite among jewelry enthusiasts. However, like any fine jewelry, they require specific care to maintain their luster and integrity.

Why is Proper Care Important?

Gold pearl necklaces are an investment, both financially and sentimentally. Neglecting their care can lead to irreversible damage, such as tarnishing of the gold or deterioration of the pearls. Regular maintenance not only enhances their appearance but also extends their lifespan, allowing you to enjoy these exquisite pieces for years to come.

Cleaning Techniques for Gold Pearl Necklaces

- Gentle Cleaning: Use a soft, lint-free cloth to gently wipe down your necklace after each wear. This removes oils and dirt that can accumulate.

- Soapy Water Solution: For deeper cleaning, mix mild soap with lukewarm water. Dip a soft cloth into the solution, wring it out, and gently wipe the pearls and gold components.

- Avoid Harsh Chemicals: Never use harsh cleaners or abrasives, as they can damage the delicate surface of pearls and gold.

Storage Tips for Gold Pearl Necklaces

Proper storage is crucial to prevent tangling and scratching. Here are some effective storage solutions:

- Soft Pouches: Store your necklace in a soft pouch made of silk or cotton to protect it from dust and scratches.

- Jewelry Boxes: Use a dedicated jewelry box with separate compartments to keep your gold pearl necklace safe from other pieces that may cause damage.

- Avoid Humidity: Keep your jewelry in a cool, dry place, as excessive humidity can harm both pearls and gold.

Preventing Damage

To further protect your gold pearl necklace, consider these preventive measures:

- Limit Exposure: Avoid wearing your necklace while swimming, showering, or exercising, as exposure to chlorine, saltwater, and sweat can cause damage.

- Apply Products Wisely: Always apply perfumes, lotions, and hairsprays before putting on your necklace to prevent residue buildup.

Professional Maintenance

For deeper cleaning and maintenance, consider taking your gold pearl necklace to a professional jeweler. They can provide thorough cleaning, check for any loose pearls, and ensure the integrity of the gold clasps and links.

In summary, the care and maintenance of gold pearl necklaces are crucial for preserving their beauty and ensuring they remain treasured items in your jewelry collection. By implementing gentle cleaning techniques, proper storage solutions, and preventive measures, you can maintain the elegance of your gold pearl necklaces for generations to come.

Cleaning Techniques

Gold pearl necklaces are not only exquisite pieces of jewelry but also require proper care to maintain their beauty over time. One of the most important aspects of caring for these luxurious necklaces is understanding effective cleaning techniques. Regular maintenance ensures that the luster of gold pearl necklaces is preserved, preventing the buildup of dirt and oils that can dull their appearance.

Gold pearl necklaces can accumulate oils from skin, dust, and environmental pollutants. This buildup can lead to a loss of shine, making the necklace appear lackluster. Regular cleaning is essential not only to maintain the visual appeal but also to extend the lifespan of the jewelry. By adopting gentle cleaning methods, you can ensure that your necklace remains a treasured piece in your collection.

When it comes to cleaning gold pearl necklaces, it is crucial to use gentle methods to avoid damaging the pearls or the gold. Here are some effective techniques:

- Soft Cloth Wipe: Use a soft, lint-free cloth to gently wipe the pearls and gold chain after each wear. This simple step can remove oils and dirt, keeping your necklace looking fresh.

- Warm Soapy Water: For a more thorough cleaning, mix a few drops of mild dish soap with warm water. Dip a soft cloth into the solution, wring it out, and gently wipe the necklace. Avoid soaking the pearls, as excessive moisture can damage them.

- Avoid Harsh Chemicals: Steer clear of abrasive cleaners, bleach, or ammonia-based products. These can harm the delicate surface of pearls and tarnish the gold.

- Rinse and Dry: After cleaning, use a clean, damp cloth to remove any soap residue. Then, lay the necklace flat on a soft towel to air dry completely before storing it.

While regular at-home cleaning is essential, consider having your gold pearl necklace professionally cleaned once a year. Jewelers have specialized tools and solutions that can safely clean and polish your jewelry, restoring its original shine. This is particularly beneficial for necklaces with intricate designs or settings that may be difficult to clean thoroughly at home.

Proper storage is equally important for maintaining the cleanliness and condition of gold pearl necklaces. Here are some tips to keep your jewelry safe:

- Use Soft Pouches: Store your necklace in a soft pouch or a dedicated jewelry box to prevent scratches and tangling with other pieces.

- Avoid Excessive Moisture: Keep your jewelry in a dry place, as excessive moisture can lead to tarnishing of gold and damage to pearls.

- Separate Storage: If possible, store your gold pearl necklace separately from other jewelry to avoid scratches and maintain its pristine condition.

By implementing these cleaning techniques and storage tips, you can ensure that your gold pearl necklace remains a stunning accessory for years to come. Regular care not only enhances its beauty but also makes it a cherished heirloom to pass down through generations.

Storage Tips

Storing your gold pearl necklaces correctly is crucial for maintaining their beauty and ensuring their longevity. Proper storage not only prevents physical damage but also preserves the luster and elegance of the pearls. Here are some essential tips to help you store your gold pearl necklaces effectively:

- Use Soft Pouches: When it comes to storage, using soft pouches made of fabric is highly recommended. These pouches provide a protective layer that prevents scratches and minimizes the risk of tangling. Avoid using plastic bags, as they can trap moisture and lead to tarnishing or damage to the pearls.

- Dedicated Jewelry Boxes: Invest in a dedicated jewelry box that is lined with soft materials. This will not only keep your necklaces organized but also protect them from dust and environmental factors. Make sure the box has individual compartments to prevent the necklaces from rubbing against each other, which can cause scratches.

- Avoid Direct Sunlight: Store your gold pearl necklaces in a cool, dark place away from direct sunlight. Prolonged exposure to sunlight can fade the color of the pearls and weaken the string or clasp over time.

- Keep Away from Chemicals: Pearls are sensitive to chemicals, including those found in household cleaning products, perfumes, and hair sprays. Always store your necklaces away from these substances to prevent damage.

- Regularly Check for Damage: Periodically inspect your gold pearl necklaces for any signs of wear and tear. Look for loose clasps, frayed strings, or discoloration. Addressing these issues promptly can prevent further damage and keep your necklaces in pristine condition.

- Separate Storage for Different Jewelry: If you have other types of jewelry, ensure that your gold pearl necklaces are stored separately. Mixing them with other jewelry can lead to scratches or tangling. Use individual compartments or separate boxes for different pieces.

By following these storage tips, you can ensure that your gold pearl necklaces remain in excellent condition for years to come. Proper storage is not just about preventing damage; it’s also about maintaining the sentimental value and beauty of these luxurious pieces. Remember, a little care goes a long way in preserving your jewelry.

Popular Trends in Gold Pearl Necklaces

Gold pearl necklaces have long been a staple of elegance and sophistication in the world of jewelry. However, as fashion continues to evolve, so do the trends surrounding these classic pieces. Staying updated on popular trends in gold pearl necklaces can help you choose pieces that are not only timeless but also fashionable and in line with current styles. This article delves into the latest trends, offering insights into how to incorporate them into your jewelry collection.

One of the most prominent trends in recent years is the art of layering necklaces. This technique allows wearers to create a unique and personalized look by combining gold pearl necklaces with other styles. Here are some tips for mastering this trend:

- Mix lengths: Combine necklaces of varying lengths to create depth and interest.

- Incorporate different materials: Pair gold pearl necklaces with chains, gemstones, or other metals to enhance visual appeal.

- Balance simplicity and complexity: Use a simple strand as a base and layer it with more intricate designs to achieve a harmonious look.

Layering not only showcases your personal style but also allows for versatility, making it suitable for both casual and formal occasions.

Another exciting trend is the mixing of materials. Contemporary designs often incorporate pearls with other elements, such as gemstones or alternative metals. This blending creates a striking contrast that appeals to modern fashion sensibilities. Here are some combinations to consider:

- Pearls and gemstones: Adding colorful gemstones can bring vibrancy and personality to a gold pearl necklace.

- Metal accents: Incorporating mixed metals—such as silver or rose gold—can create a chic and trendy look.

- Textured finishes: Combining smooth pearls with textured chains or beads adds dimension to your jewelry.

Personalization is a growing trend in the jewelry industry, and gold pearl necklaces are no exception. Customized designs allow wearers to express their individuality through their jewelry choices. Consider these options when looking for a personalized piece:

- Selecting pearl types: Choose from various pearl types, such as freshwater, Akoya, or Tahitian, to match your style.

- Adjusting lengths: Customizing the length of the necklace ensures it fits perfectly with your neckline and style preferences.

- Adding initials or charms: Incorporating personal elements, such as initials or meaningful charms, can make the necklace one-of-a-kind.

Fashion often recycles trends, and gold pearl necklaces are experiencing a resurgence of vintage and retro influences. This trend embraces the elegance of past eras while adding a modern twist. Here’s how to incorporate vintage elements:

- Art Deco styles: Look for designs that feature geometric shapes and intricate details reminiscent of the Art Deco period.

- Classic motifs: Incorporate designs that reflect vintage floral patterns or intricate filigree work.

- Antique finishes: Opt for necklaces with an aged or patinated look for a genuine vintage feel.

In contrast to minimalist styles, bold and statement-making gold pearl necklaces are gaining popularity. These pieces often feature oversized pearls or unique designs that draw attention. Here are some tips for wearing statement pieces:

- Keep the outfit simple: Allow the necklace to be the focal point by wearing it with understated clothing.

- Experiment with asymmetry: Choose designs that feature asymmetrical layouts for a modern touch.

- Layer with caution: When layering, ensure the statement piece remains prominent by balancing it with simpler designs.

By staying informed about these popular trends in gold pearl necklaces, you can choose pieces that not only reflect your personal style but also align with contemporary fashion. Whether you prefer classic elegance or bold statements, there is a gold pearl necklace trend to suit every taste.

Layering Necklaces

has become a fashionable way to express individuality and creativity through jewelry. This trend allows wearers to combine different styles, lengths, and materials, resulting in a unique and personalized look. Among the most popular choices for layering are gold pearl necklaces, which add a touch of elegance and sophistication to any ensemble. In this article, we will explore the art of layering necklaces, the best combinations to try, and tips for achieving a balanced and stylish appearance.

Layering necklaces is not just about wearing multiple pieces; it’s about creating a harmonious look that enhances your outfit. The key is to mix and match various lengths, styles, and materials to achieve a balanced effect. For instance, pairing a gold pearl necklace with a delicate chain can create a stunning contrast, while incorporating different textures can add depth to your overall appearance.

- Gold Pearl Necklaces: These classic pieces serve as a beautiful foundation for layering. Their timeless appeal makes them versatile for both casual and formal occasions.

- Delicate Chains: Thin, simple chains can provide a minimalist touch that complements the richness of gold pearls.

- Statement Pieces: Bold necklaces can serve as focal points in your layered look, drawing attention and adding personality.

To achieve a stunning layered necklace look, consider the following tips:

- Vary the Lengths: Mix necklaces of different lengths to create visual interest. For example, a short gold pearl necklace paired with a longer pendant necklace can create a beautiful cascading effect.

- Mix Materials: Combining gold pearls with other materials such as leather, beads, or gemstones can add texture and uniqueness to your layers.

- Balance the Weight: Ensure that the weight of your necklaces is balanced. Pair heavier pieces with lighter ones to avoid overwhelming your neckline.

Layering necklaces can be adapted for various occasions:

- Casual Outings: For a relaxed look, try layering a gold pearl necklace with a simple chain and a beaded necklace. This combination is perfect for brunch or a day out with friends.

- Formal Events: Elevate your evening attire by layering a gold pearl necklace with a statement piece. This can create a sophisticated and elegant look for weddings or formal dinners.

- Everyday Wear: For a chic everyday style, consider layering a delicate gold pearl necklace with a couple of shorter chains. This subtle look can easily transition from day to night.

Proper care is essential to keep your layered necklaces looking their best. Here are some maintenance tips:

- Regular Cleaning: Clean your necklaces regularly to remove dirt and oils. Use a soft cloth for gold pearl necklaces and a gentle jewelry cleaner for other materials.

- Safe Storage: Store your necklaces separately to prevent tangling and scratching. Use a jewelry box with compartments or individual pouches for each piece.

- Avoiding Damage: Remove your necklaces before swimming or exercising to prevent exposure to chlorine or sweat, which can damage the materials.

In conclusion, layering gold pearl necklaces with other types of jewelry is a fantastic way to showcase personal style and make a bold statement. By understanding the art of layering, choosing the right combinations, and properly maintaining your jewelry, you can create stunning looks that reflect your individuality and enhance your outfits.

Mixing Materials

in jewelry design has gained immense popularity in recent years, particularly in the realm of gold pearl necklaces. This trend not only adds a distinctive flair but also enhances the overall aesthetic appeal of these luxurious pieces. By integrating various materials such as gemstones and metals, designers create unique combinations that cater to modern fashion sensibilities.

One of the most compelling aspects of is the textural contrast it offers. For instance, pairing lustrous pearls with the sparkle of diamonds or the vibrant hues of colored gemstones can create a visually striking effect. This combination not only elevates the elegance of gold pearl necklaces but also allows for a more personalized expression of style. Each piece becomes a canvas for creativity, reflecting the wearer’s individuality.

Moreover, the integration of metals like silver or rose gold alongside traditional yellow gold can introduce a contemporary edge to classic designs. This versatility enables wearers to transition their jewelry from day to night effortlessly, making them suitable for various occasions. For example, a gold pearl necklace accented with silver links can be worn casually with a simple blouse or dressed up for an evening event with a chic dress.

In addition to aesthetics, mixing materials can also enhance the durability of jewelry. Different materials can provide structural support, ensuring that the necklace withstands daily wear and tear. For instance, incorporating a sturdy metal clasp or chain can prevent breakage while maintaining the gracefulness of the pearls. This blend of form and function is particularly appealing to modern consumers who prioritize both style and practicality.

When considering a gold pearl necklace that features mixed materials, it’s essential to choose pieces that harmonize well together. A well-thought-out design will ensure that the elements complement rather than compete with each other. For example, a necklace that combines creamy white pearls with soft pink rose gold can create a cohesive look that feels both sophisticated and fresh.

Furthermore, the trend of mixing materials allows for greater creativity in customization. Many jewelers now offer bespoke services, enabling clients to select their desired combination of pearls, metals, and gemstones. This personalized approach not only results in a one-of-a-kind piece but also fosters a deeper emotional connection between the wearer and their jewelry.

As consumers continue to seek unique and meaningful jewelry, the trend of mixing materials in gold pearl necklaces is likely to endure. This approach not only reflects personal style but also embraces the spirit of innovation in the jewelry industry. With endless possibilities for customization and design, mixing materials offers an exciting avenue for both jewelry designers and enthusiasts alike.

The Symbolism of Pearls in Jewelry

Pearls have long been associated with various meanings and symbolism in jewelry, adding depth to the significance of gold pearl necklaces beyond their aesthetic appeal. This elegant gemstone is not just a beautiful adornment; it carries a rich tapestry of meanings that resonate with people across cultures and generations. In this section, we will delve into the profound symbolism of pearls, exploring their connections to purity, wisdom, love, and loyalty.

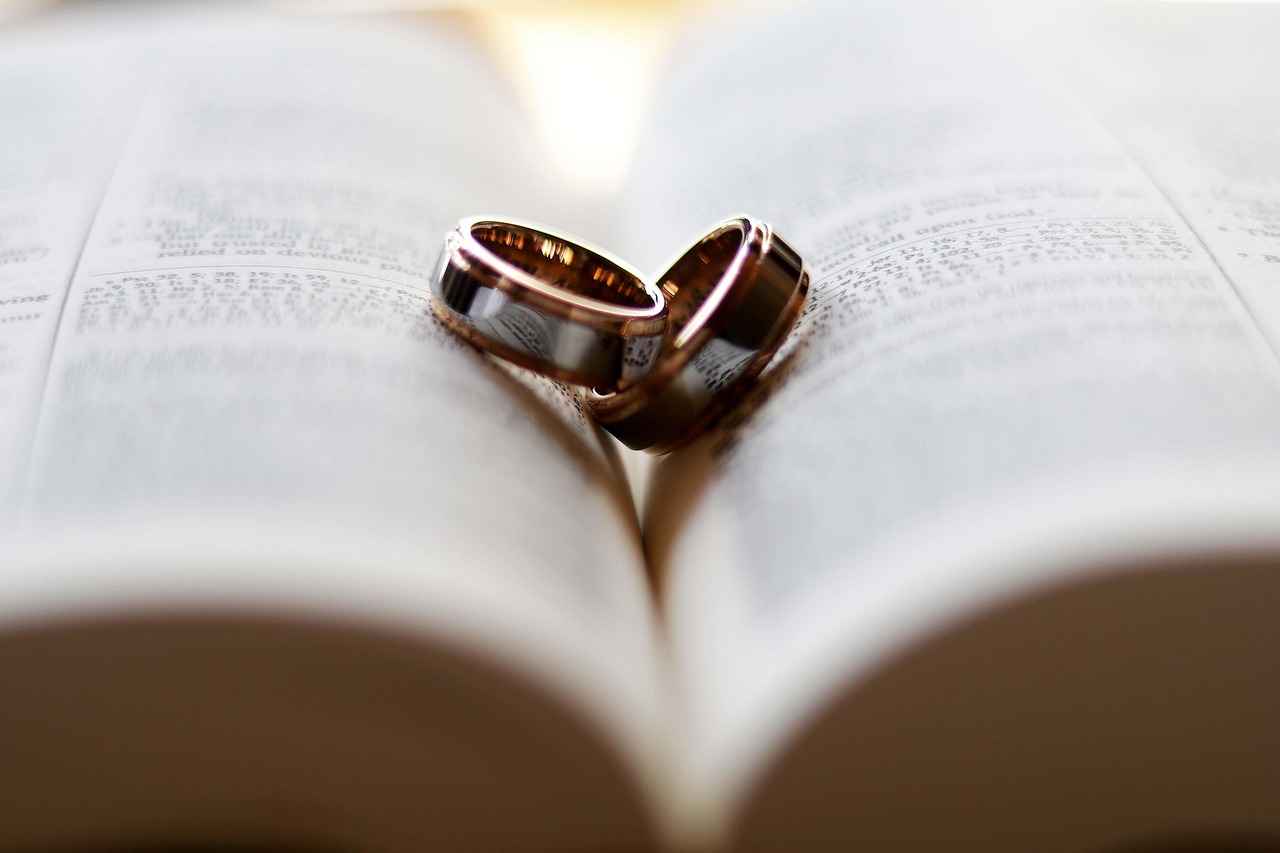

Pearls have been cherished throughout history, often regarded as symbols of purity and innocence. Their unique formation process, which involves an oyster’s natural defense against irritants, adds to their mystique. This transformation from a simple grain of sand to a lustrous gem mirrors the journey of personal growth and enlightenment. Many cultures have embraced this symbolism, making pearls a popular choice for bridal jewelry, representing the purity and commitment of marriage.

In addition to purity, pearls are also linked to wisdom. Ancient civilizations believed that pearls could impart wisdom and promote emotional balance. This belief has persisted through the ages, making pearl jewelry a thoughtful gift for graduates, new mothers, or anyone embarking on a new chapter in life. Wearing a gold pearl necklace can serve as a daily reminder of one’s own journey of learning and growth.

Furthermore, pearls have a significant place in the realm of love and loyalty. In many cultures, they symbolize deep emotional connections and fidelity. Gifting a pearl necklace can signify a promise of love and devotion, making it a popular choice for anniversaries and special occasions. The timeless beauty of pearls enhances their meaning, as they age gracefully, much like enduring relationships.

- Purity and Innocence: Pearls are often associated with purity, making them a popular choice for bridal jewelry.

- Wisdom: Historically, pearls have been believed to impart wisdom and emotional balance.

- Love and Loyalty: Pearls symbolize deep emotional connections, making them ideal gifts for significant milestones.

Moreover, pearls are often seen as a representation of feminine energy. Their soft luster and smooth texture evoke feelings of grace and elegance. Many women choose to wear pearl jewelry not only for its beauty but also for the empowering symbolism it carries. It serves as a reminder of the strength found in vulnerability and the beauty that comes from embracing one’s true self.

In modern times, the significance of pearls has evolved, yet their core symbolism remains intact. They are increasingly viewed as versatile pieces that can be worn for both formal and casual occasions, symbolizing adaptability and timelessness. This duality allows gold pearl necklaces to fit seamlessly into any wardrobe, resonating with the wearer’s personal story.

In conclusion, the symbolism of pearls in jewelry extends far beyond their visual appeal. With meanings tied to purity, wisdom, love, loyalty, and feminine energy, gold pearl necklaces serve as meaningful accessories that reflect the wearer’s journey and relationships. Whether given as a gift or worn as a personal statement, the significance of pearls enriches their beauty, making them cherished pieces in any jewelry collection.

Purity and Wisdom

When it comes to jewelry, few pieces carry the emotional weight and significance that gold pearl necklaces do. Among the myriad of meanings associated with pearls, their representation of purity and wisdom stands out, making them a cherished choice for gifts and personal adornment alike.

Pearls have been revered throughout history as symbols of purity. This association stems from their natural formation, which occurs when an irritant enters an oyster’s shell, prompting the mollusk to secrete layers of nacre to coat the irritant. Over time, this process results in the creation of a lustrous pearl. This transformation from an irritant to a beautiful gem is often seen as a metaphor for personal growth and spiritual enlightenment.

The purity of pearls is not merely a physical attribute; it is imbued with deeper meanings. In many cultures, pearls are believed to bring clarity and tranquility to the wearer, enhancing their inner peace and promoting a sense of calm. This makes gold pearl necklaces not only a fashionable accessory but also a source of emotional support, particularly during significant life events such as weddings or graduations.

In addition to purity, pearls are often linked to wisdom. This connection is particularly prevalent in various cultural narratives and myths. For instance, in ancient traditions, pearls were thought to bestow wisdom upon the wearer, making them a favored gift for those embarking on new journeys or facing important life decisions. The idea is that pearls, having undergone a transformative process, represent the lessons learned through experience and the wisdom that comes with time.

Wearing a gold pearl necklace can serve as a reminder of the value of knowledge and the importance of learning from one’s experiences. This is especially meaningful for individuals stepping into new phases of their lives, such as starting a new career or becoming a parent. The necklace can symbolize the journey of personal growth and the wisdom gained along the way.

Given their associations with purity and wisdom, gold pearl necklaces make for thoughtful gifts on special occasions. Whether it’s a graduation, a wedding, or a milestone birthday, these necklaces can convey heartfelt sentiments that resonate deeply with the recipient. The emotional value attached to pearls enhances their significance, making them more than just a piece of jewelry; they become a cherished keepsake filled with meaning.

When selecting a gold pearl necklace as a gift, consider the recipient’s personal style and the message you wish to convey. A simple strand may symbolize purity and elegance, while a more intricate design might represent the complexity of wisdom gained through life’s experiences. This personalization adds an extra layer of thoughtfulness, ensuring that your gift is not only beautiful but also meaningful.

In summary, the symbolism of purity and wisdom associated with pearls enhances the emotional value of gold pearl necklaces. These timeless pieces are not only aesthetically pleasing but also serve as powerful reminders of personal growth and the importance of inner clarity. Whether worn as a personal adornment or given as a gift, gold pearl necklaces carry a message that resonates on a profound level, making them a treasured addition to any jewelry collection.

Love and Loyalty

Gold pearl necklaces are not only exquisite pieces of jewelry but also carry profound meanings that resonate deeply across various cultures. Among these meanings, the concepts of love and loyalty stand out prominently, making them ideal gifts for commemorating significant relationships and milestones in life.

Throughout history, pearls have been celebrated for their beauty and rarity. In many cultures, they symbolize love, often being associated with romantic relationships and cherished connections. The soft, lustrous glow of pearls is reminiscent of the gentle and nurturing aspects of love, making them a perfect choice for gifts that signify deep emotional bonds. Whether given as a wedding gift, an anniversary present, or a token of appreciation, a gold pearl necklace serves as a lasting reminder of affection and commitment.

In addition to love, pearls also embody the idea of loyalty. Their formation process is a testament to resilience and dedication. Just as a pearl is formed through layers of nacre deposited around a grain of sand, loyalty is built through trust and consistent support in relationships. This symbolism enhances the emotional value of gold pearl necklaces, making them not just beautiful accessories but also meaningful tokens of enduring loyalty.

Many couples choose to exchange gold pearl necklaces during significant milestones, such as engagements or anniversaries. This practice is rooted in the belief that pearls enhance love and strengthen the bonds between partners. The act of gifting a pearl necklace is often seen as a promise to cherish and remain loyal to one another, reinforcing the idea that true love is both precious and enduring.

Furthermore, the versatility of gold pearl necklaces allows them to be worn on various occasions, symbolizing love and loyalty in everyday life. Whether paired with casual attire or worn as part of formal wear, these necklaces serve as constant reminders of the relationships that matter most. The blend of gold and pearls creates a timeless elegance that transcends fashion trends, ensuring that the sentiment behind the jewelry remains relevant through the years.

In many cultures, pearls are also considered lucky, further enhancing their significance as gifts for loved ones. This belief adds an extra layer of meaning, as the act of giving a gold pearl necklace is not only a gesture of love but also a wish for prosperity and happiness in the recipient’s life.

In conclusion, the symbolism of love and loyalty embedded in gold pearl necklaces makes them exceptional gifts for commemorating life’s significant moments. Their beauty, combined with the deep meanings they carry, ensures that these necklaces remain cherished pieces in any jewelry collection, representing the enduring bonds we share with our loved ones.

Where to Buy Gold Pearl Necklaces

Finding the right retailer for gold pearl necklaces is essential for ensuring quality and authenticity, whether you prefer shopping online or in physical stores. With the increasing popularity of these exquisite jewelry pieces, the market is filled with numerous options. However, not all retailers offer the same level of craftsmanship, customer service, or guarantees. Below are some key considerations to help you make an informed decision.

Shopping for gold pearl necklaces online provides unparalleled convenience. You can browse a wide variety of styles, compare prices, and read customer reviews all from the comfort of your home. However, it is crucial to choose reputable online retailers. Look for websites that offer detailed product descriptions, high-resolution images, and customer testimonials.

- Quality Certifications: Ensure the retailer provides certifications for their pearls and gold, verifying their authenticity.

- Return Policies: A good return policy allows you to return or exchange the necklace if it does not meet your expectations.

- Customer Support: Responsive customer service can assist with inquiries and provide peace of mind during your shopping experience.

Visiting local jewelers offers a unique experience that online shopping cannot replicate. You can see and feel the jewelry in person, ensuring that the quality meets your standards. Local jewelers often provide personalized service, helping you find the perfect piece that fits your style and budget.

- Expert Guidance: Local jewelers can offer expert advice on the best styles and care techniques for your gold pearl necklace.

- Customization Options: Many local stores offer customization, allowing you to create a unique piece that reflects your personality.

- Supporting Local Businesses: Purchasing from local jewelers supports your community and helps sustain small businesses.

Whether you are shopping online or in-store, there are several critical factors to consider when purchasing a gold pearl necklace:

- Type of Pearls: Understand the different types of pearls, such as freshwater, saltwater, or cultured, as they vary in quality and price.

- Gold Quality: Look for necklaces made with high-quality gold, such as 14k or 18k, to ensure durability and longevity.

- Design and Style: Consider your personal style and how the necklace will complement your existing jewelry collection.

When investing in a gold pearl necklace, authenticity is paramount. Always ask for documentation proving the quality of the pearls and gold. Reputable retailers will provide this information without hesitation. Additionally, consider purchasing from well-known brands or jewelers with positive reputations in the industry.

In summary, finding the right retailer for gold pearl necklaces involves careful consideration of both online and local options. By understanding what to look for and prioritizing quality and authenticity, you can make a purchase that you will cherish for years to come. Whether you prefer the convenience of online shopping or the personal touch of local jewelers, the perfect gold pearl necklace is waiting for you.

Online Retailers vs. Local Jewelers

When it comes to purchasing a stunning gold pearl necklace, the choice between online retailers and local jewelers can significantly impact your shopping experience. Each option presents its own unique advantages, making it essential to understand what they offer to make an informed decision.

Online shopping has revolutionized the way we buy jewelry. The convenience of browsing through countless options from the comfort of your home cannot be overstated. With just a few clicks, you can access a vast selection of gold pearl necklaces, often at competitive prices. Online retailers frequently provide detailed product descriptions, high-quality images, and customer reviews, which can help you gauge the quality and appeal of a piece before making a purchase.

Moreover, many online platforms offer exclusive deals and discounts that you might not find in physical stores. This can be particularly beneficial for those looking to acquire a beautiful necklace without breaking the bank. Additionally, the ability to compare prices across different websites allows you to find the best possible deal.

However, purchasing jewelry online does come with its challenges. One major drawback is the inability to physically inspect the necklace before buying. While images can be high-quality, they may not capture the true color, luster, or craftsmanship of the piece. There is also the concern of authenticity; ensuring that the pearls and gold are genuine can be more difficult when shopping online.

On the other hand, local jewelers provide a more personalized shopping experience. Visiting a physical store allows you to see, touch, and try on the gold pearl necklaces, giving you a better sense of how they will look and feel. Local jewelers often pride themselves on their expertise and can offer valuable insights into the quality of the materials used, as well as styling tips that suit your personal taste.

Furthermore, local jewelers can create a sense of trust and community. Building a relationship with a jeweler can lead to a more fulfilling shopping experience. They may offer customization options, allowing you to design a unique piece that reflects your style and preferences. This level of service is often unmatched by online retailers.

However, the selection at local jewelers may be limited compared to what you can find online. Additionally, prices might be higher due to overhead costs associated with running a physical store. It’s essential to weigh these factors when deciding where to purchase your gold pearl necklace.

Ultimately, the choice between online retailers and local jewelers depends on your personal preferences. If you value convenience and a broad selection, online shopping may be the best option for you. Conversely, if you prefer a hands-on approach and personalized service, visiting a local jeweler could be the ideal choice. By understanding the strengths and weaknesses of both options, you can ensure that your purchase of a gold pearl necklace is a satisfying and rewarding experience.

What to Look For

When embarking on the journey of purchasing a gold pearl necklace, there are several critical factors that you need to consider to ensure that you make a wise investment. This guide will help you navigate through the essential aspects of buying a gold pearl necklace, focusing on quality certifications, return policies, and customer reviews.

- Quality Certifications: One of the most important aspects to check when buying a gold pearl necklace is the quality certification. Look for certifications from reputable organizations that guarantee the authenticity and quality of the pearls and gold used in the necklace. Certifications such as the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) or the American Gem Society (AGS) can provide assurance of the necklace’s quality.

- Return Policies: Understanding the return policy of the retailer is crucial. A good return policy allows you to return the necklace if it does not meet your expectations. Check if the retailer offers a money-back guarantee or an exchange policy. This is especially important for online purchases, where you cannot physically inspect the necklace before buying.

- Customer Reviews: Customer reviews are a valuable resource when purchasing jewelry. They provide insights into the experiences of other buyers, helping you gauge the quality and service of the retailer. Look for detailed reviews that discuss the quality of the necklace, customer service experiences, and any issues encountered during the purchase process.

In addition to these factors, consider the following:

- Design and Style: The design of the necklace should resonate with your personal style. Whether you prefer a classic strand or a more contemporary design, ensure that the necklace complements your wardrobe.

- Price Point: Establish a budget before you start shopping. Gold pearl necklaces can vary significantly in price based on the quality of the pearls and the craftsmanship involved. Make sure you are getting value for your money.

- Seller Reputation: Research the reputation of the seller. Look for retailers with a long-standing history in the jewelry industry. A reputable seller is more likely to provide high-quality products and excellent customer service.

By keeping these factors in mind, you can confidently select a gold pearl necklace that not only meets your aesthetic preferences but also stands the test of time in quality and craftsmanship. Investing in a gold pearl necklace is not just about the purchase; it’s about finding a piece that will be cherished for years to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What are gold pearl necklaces made of?

Gold pearl necklaces typically consist of high-quality pearls, which can be natural or cultured, and are strung together with gold accents or chains. The gold can vary in karat quality, affecting both the necklace’s appearance and value.

- How do I choose the right gold pearl necklace for an occasion?

When selecting a gold pearl necklace, consider the occasion and your personal style. For formal events, a classic strand or multi-strand design works beautifully, while contemporary styles may be perfect for casual outings. Versatility is key!

- What is the best way to care for my gold pearl necklace?

To maintain the beauty of your gold pearl necklace, gently clean it with a soft cloth after each wear to remove oils and dirt. Store it in a soft pouch or a dedicated jewelry box to prevent scratches and tangling.

- Are there any current trends in gold pearl necklaces?

Absolutely! Layering gold pearl necklaces with other jewelry is a hot trend right now. Mixing materials, like combining pearls with gemstones or metals, also adds a unique flair that many fashion enthusiasts love.

- Where can I buy a quality gold pearl necklace?

You can find quality gold pearl necklaces at both online retailers and local jewelers. Online shopping offers convenience, while local jewelers provide personalized service and the chance to see the pieces up close.