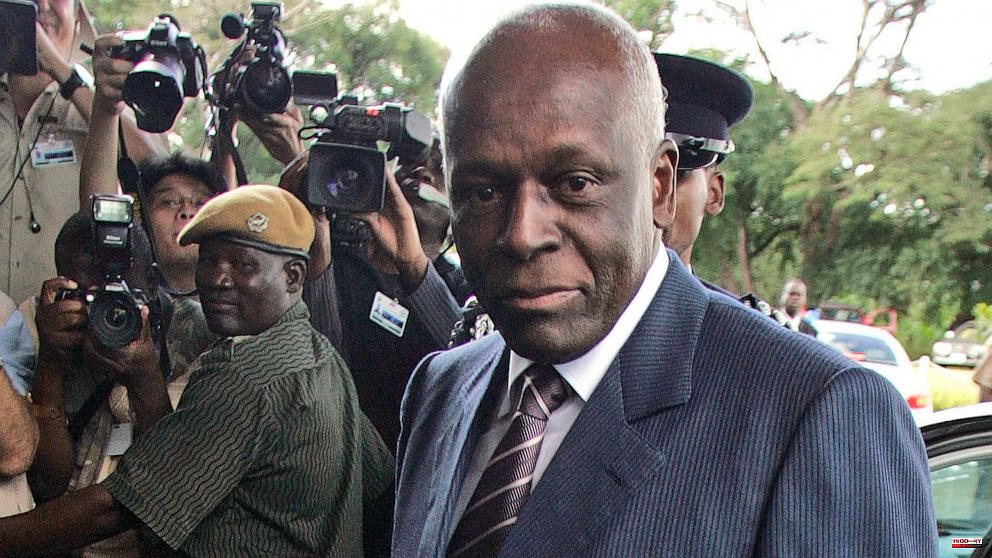

LISBON (Portugal) -- Jose Eduardo dos Santos was once Africa's longest-serving ruler. He led Angola through the longest civil war in Africa and made his country a major oil producer, as well as one the poorest and most corrupt countries in the world, for almost forty years. He was 79 years old.

Dos Santos, who had been ill for a while, died in a Barcelona clinic, Spain. The Angolan government posted the news on its Facebook page.

According to the announcement, dos Santos was a "stateman of great historical significance who governed... Angola through very difficult times."

Dos Santos, who had lived in Barcelona most of his life since his retirement in 2017, had been receiving treatment for various health issues there.

Joao Lourenco (current head of Angola's state) announced Friday's five-day national mourning. The flag of the country will be flown at half-staff, and all public events will be canceled.

His spokesperson said that U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres remembered dos Santos participation in the struggle for Angola's independence. He also led the signing of the peace accord that ended the civil war in 2002. "Angola was an important regional and global partner, and advocate for multilateralism during his tenure."

At the beginning of Friday's meeting, the U.N. Security Council paid silent tribute to dos Santoss after Brazil's current president, the U.N. Ambassador Ronaldo Costa Filho expressed his "sadness” at his passing.

Four years after Angola was independent from Portugal, Dos Santos became involved in the Cold War as a proxy warground.

His political career included single-party Marxist rule during post-colonial times and a democratic government system adopted in 2008. When his health began to decline, he voluntarily decided to step down.

Dos Santos, who was often unassuming and shy in public, could be seen as unassuming. He was an intelligent operator behind the scenes.

To maintain his grip on Luanda's 17th-century presidential palace, the country's Atlantic capital in southern Africa, he divided Angola's wealth among his army generals and political opponents to ensure their loyalty. He degraded anyone who he felt was gaining popularity that could pose a threat to his command.

Jonas Savimbi was Dos Santos’ greatest foe for over two decades. He is the leader of the UNITA rebels. His post-independence insurgency fought against the bush and aimed to expel dos Santos’ Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (or MPLA).

The Soviet Union provided financial and military support to the MPLA in their war against UNITA. The United States and South Africa supported Savimbi.

The war would continue, with brief periods U.N.-brokered calm until 2002, when Savimbi was finally captured in eastern Angola by the army and killed.

After the collapse of Soviet Union in early 1990s, Dos Santos suddenly abandoned his Marxist policies. He moved closer towards Western countries, where oil companies have invested billions in offshore exploration.

His admirers praised his ability adapt to changing situations. Critics called him inept.

Dos Santos was invited by George W. Bush to the White House in 2004 as the United States sought to reduce its dependence upon oil from the Middle East.

Angola was the second-largest sub-Saharan African oil producer after Nigeria. It produced close to 2,000,000 barrels per day. Each year, it also discovered more than $1 billion worth diamonds.

The Angolan people were not able to access the wealth. They were exposed to large unmapped minefields, and had limited access and basic amenities such as roads and running water. The country was poor in education and health care.

According to the U.S. State Department, Angola's wealth is concentrated in the hands of small elites who use government positions for huge personal enrichment.

Dos Santos was thought to have valuable real estate in Brazil and France, as well foreign bank accounts.

His rule was a blessing in disguise, and street protests were very rare, despite widespread poverty. The heavily armed riot police, known as the "Ninjas", quickly broke up the demonstrations and quickly dispersed them. A well-paid, well-equipped presidential guard was stationed in dos Santos’s palace, and lined the streets of the city's poor, potholed streets when he emerged.

Dos Santos, a bricklayer's son, was born in Luanda, Angola's capital. He began his political career in 1961 with boots and a rifle as an 18-year old guerrilla for MLPA, fighting for Portugal's independence.

In 1963, his MPLA bosses rescued him from combat and sent him to the Soviet Union to train as a military communications specialist and petroleum engineer.

He returned to Angola in 70 and negotiated compromises to prevent the MPLA's disintegration. As a reward, he was elected to the central committee of the party.

Dos Santos was appointed foreign minister, later planning minister, and deputy prime minster in the single-party Marxist government upon independence in 1975.

Surprise choice: the MPLA elected dos Santos, 37, as president after Agostinho Neto, Angola’s first leader, died in 1979. Dos Santos was viewed as a consensus figure among squabbling party veterans but few expected his political longevity.

Dos Santos did not seek to create a personality cult, and he remained a mystery figure. According to reports, he once stated in private that he believed his true calling was to be a monk.

He was also not known for his political sensibility: He built a multimillion dollar mansion in Luanda shantytown, while millions of Angolans starved during civil war.

After a 1992 peace treaty, he was seen as a certain loser in the country's first democratic election.

Margaret Anstee, an ex-special representative of the U.N. to Angola, described dos Santos almost as the opposite of Savimbi.

"His demeanor seemed grave and reserved. I felt a feeling of shyness or timidity. This was absurd. She wrote that Dr. Savimbi's fiery personality was a stark contrast to hers in "Orphan of Cold War," her 1996 book about Angola.

Dos Santos remained strong and won again the election, narrowly beating Savimbi to the presidency seat. The MPLA was also elected the parliamentary majority in the concurrent legislative election.

After Savimbi rejected defeat at the ballot box, he returned to his armed struggle and Western support slowly shifted towards dos Santos.

In 1994, the United Nations brokered another peace agreement between the foes, which was also dissolved four years later.

Dos Santos, an army of approximately 100,000 soldiers, many of whom have years of experience in jungle combat, began to play a role of a regional power broker with neighbouring countries.

In 1997, he sent 2,500 troops to Republic of Congo to assist President Denis Sassou–Nguesso in assuming power. The following year, he sent a contingent of Congolese soldiers to President Laurent Kabila's government to fight rebels supported by Rwanda and Uganda.

Angola's civil conflict ended in 2002, opening up opportunities for economic growth in the country in southern Africa. It is three times larger than California.

However, the public infrastructure was destroyed; approximately 4 million people fled their homes due to the fighting. The political and military elite continued to hold the oil and diamond riches.

Transparency International, Berlin-based, named Angola one of the 10 most corrupt countries in 2005's Corruption Perceptions Index.

John McMillan, an economist at Stanford University, wrote that "as land mine-maimed kids begged in the street, politicians' wives flew into New York on the state health budget for cosmetic surgery." He was referring to a 2005 study about corruption in Angola.

Dos Santos, under pressure to hold a vote, announced legislative elections in 2008 as well as a presidential election the next year.

The most votes for parliamentary seats were won by Dos Santos's MPLA. The head of state then changed his mind, postponing first the presidential ballot and then scrapping the election.

He changed the constitution to ensure that the president is elected by the party that wins the parliamentary elections. He remained in power for eight more years.

Dos Santos, however, announced that he would be retiring in 2016, despite his declining health.

Lourenco, a MPLA veteran, was elected to replace him. Lourenco has made anti-corruption his main policy. Lourenco has focused on dos Santos’ grown children, who have a wealth of personal assets that rivals his predecessor.

One of dos Santos’s daughters suspects that her father died as a result of a conspiracy. Tchize Dos Santos claims that ex-presidents tried to kill him and failed to properly care for him. Police and Spanish prosecutors are investigating.

Dos Santos was four times married and survived by Ana Paula, his current wife. Ana Paula was the mother of his three children. At least three additional children and a variety of grandchildren are known to be his descendants.