Tens of thousands of the seven million displaced people, mostly women, children and older people; they transit or settle in the cities and rural areas of Uzhgorod and Ivano-Frankivsk in southwestern Ukraine and Kropivnitsky in the center of the country.

In the cities there is a greater presence of NGOs, but in rural areas there are fewer services. Many people decided where to flee because they have family or friends in the area or because shelters are available. In fact, most stay in private homes. Each district or village usually has a center where displaced people can register, and there is a list of shelters, such as schools or youth centers, where rooms (mostly shared) are available.

These places are run by local authorities with the support of volunteers and provide blankets, pillows, medicine, food and other essential items.

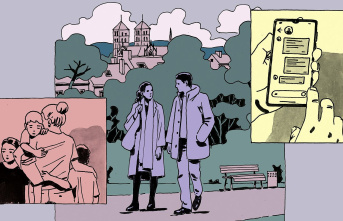

The cities have increased in population with the arrival of displaced people and sirens are heard intermittently. Fuel is rationed, people talk about bombings and deaths, and sometimes their emotions overwhelm them. They are consuming a lot of news about the war, especially through mobile. There are roadblocks and curfews, and you only see military planes in the sky, there are no others. There is no longer face-to-face education and children receive classes exclusively online.

Despite all this, there is a sense of normalcy and people continue to go about their daily business. However, the further east, the closer to the front lines, the greater the anguish. And the more recent the flight from a conflict zone, the more likely it is that the person has been exposed to a traumatic experience.

Our teams see acute symptoms of distress, people who are hyperreactive to sound, and others who are irritable or angry. Some people have intrusive thoughts or flashbacks: a person may recall an attack in their hometown every time the sirens sound.

Many are worried about what may happen in the future. Some women, for example, fear that their husbands will have to join the army. Other people are sad because their family left the country and they feel lonely. I remember a woman whose son is currently in Austria and her husband is fighting in the Donbas region. Children sometimes display aggressive or regressive behaviors, such as bedwetting.

We also see people who want to help each other because they feel the need to be helpful. Others feel guilty for being alive, for not being on the front lines, for dancing and listening to music, because they think it is not appropriate.

In Ukraine there are about 10 psychiatrists and 1 psychologist per 100,000 inhabitants, according to WHO data from 2020. There are several hospitals, many of them in remote areas, where people were hospitalized for long periods of time to receive psychological care, and where they used to treat psychological problems with medication instead of therapy.

Some psychologists are not trained in psychological first aid and there is no real referral system. In the eastern part of the country, they have more experience in emergencies due to the protracted conflict. On the other hand, professionals located in western areas, those receiving displaced people, often do not have sufficient experience in managing acute stress, and mental health support networks rely on volunteers. To this must be added a stigma associated with seeing a mental health professional, something common in many parts of the world.

In recent weeks, we have recruited professionals from this field and are now beginning to recruit community mental health workers to go door to door to attend to needs in official shelters and informal settlements.

We are training hospital and polyclinic workers, and social workers and volunteers who work in shelters for displaced people in psychological first aid. We train them on how to deal with symptoms of acute stress and on case detection. There is also a self-care component because while healthcare workers focus their priorities on their patients, they also experience high levels of stress.

We treat displaced people directly through psycho-education groups and individual consultations, either in person or by phone. Health workers and school psychologists refer patients to us who also reach us through a specific helpline. We want to help all of them better manage their symptoms and understand that their symptoms are a normal response to an abnormal situation.

=====================================

Raúl Manarte is responsible for mental health at Doctors Without Borders in Ukraine