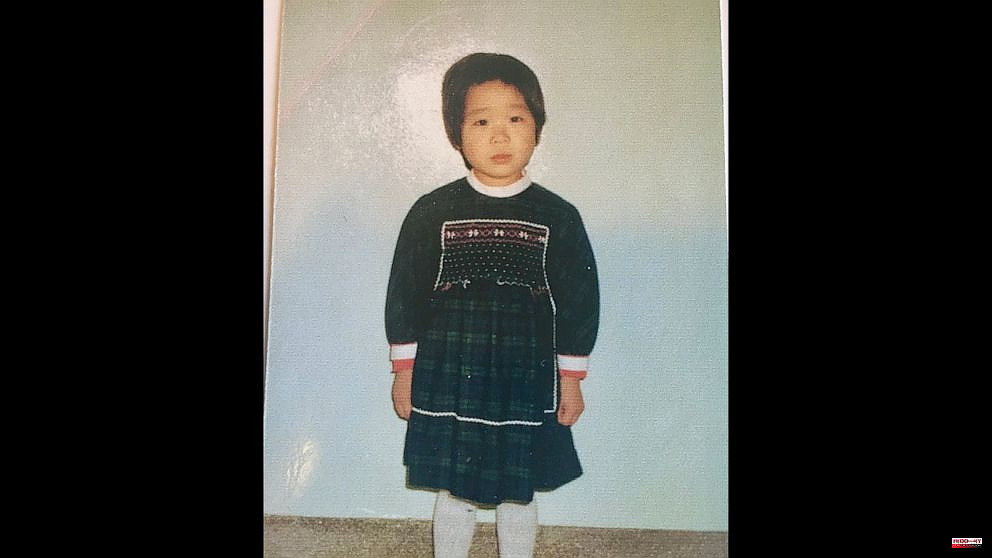

SEOUL, South Korea -- Joo-Rei Mathieson's earliest photograph of herself was taken at the age of four. Her head is shaved and her eyes are down. She just arrived in South Korea, the most dangerous place for a child.

This black-and-white mugshot was taken from a Brothers Home intake document from November 1982. It describes Mathieson, a street child who was brought in by police. It also notes that Mathieson was a vagrant facility sponsored by the government.

The document states that she was unable to speak for several days after she entered Brothers, a now-destroyed facility located in Busan's southern port city. There, thousands of children and adults were enslaved, often killed, raped, and beat in the 1970s and 80s.

Mathieson stated that she was traumatized and scared by Mathieson's reaction to herself. She pictured the emotions of Hwang Joo Rei, the girl who had been given Hwang Joo Rei due to the Juryedong district where Brothers used to be.

Mathieson was one among the fortunate ones. Mathieson and 21 other Brothers children were taken to another orphanage in the city in August 1983. Overcrowding at Brothers' sprawling compound may have allowed her escape.

Mathieson was then lured into an international adoption program that separated thousands Korean children from their families. This was part of a lucrative venture run by the military governments in South Korea that ruled from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Mathieson was given her approximate birth date, along with other details to facilitate a chaotic immigration process designed to send as many children as possible abroad. Mathieson was flown to Canada in November 1984 to see her Canadian adoptive parents. This was part of the child export frenzy which created the largest diaspora of adopted children.

Mathieson stated that she lived most of her adult years in a "tunnel view moving forward", never questioning her history and traveling the world as a Canadian before eventually settling in Hong Kong, where she worked in the hospitality sector.

In recent months, her Korean heritage "jumped back" at them as she felt she was on a mission to find her roots and locate her Korean family members if they were still alive.

In order to protect her privacy, she listed the name of her adopted children in an AP report in 2019 that reported that Brothers was involved in the adoption industry. Mathieson is willing to talk publicly now to increase her chances of finding Korean relatives, including a possible sister named Lee Chang-keun.

This name is on the adoption papers for another Korean adoptee, who was, with his younger brother in 1986, sent to a family living in Belgium. Mathieson reconnected with him last October after commercial DNA tests, increasingly used by Korean adoptees looking for reunions, revealed that they were most likely to be siblings.

Mathieson stated that it was thrilling to find a blood relative and establish a connection with her biological roots, despite not knowing her birthdate, name or hometown.

"I believe that no one on the planet, except adoptees, will be able to understand what it's like for someone to live their life without any connection to their roots." It's something normal people will take as a given," Mathieson stated in a Zoom interview. He used air quotes to describe "normal" and said that it was exciting to see someone so similar to me.

This finding raised troubling questions about her adoption and the circumstances of her newfound kin. They didn't respond directly to AP's requests.

According to his paperwork, he and his younger brother were adopted by an orphanage in Anyang. This is about 190 miles from Busan. The paperwork states that the boys were abandoned in August 1982, months prior to Mathieson's arrival. It also mentions that Lee Chang-keun was their brother and they lived at a different Anyang orphanage.

It is not mentioned if Lee was adopted. Mathieson hopes Lee stayed in Korea, and that she can find him. She is desperate to find out more about her Korean parents and how they separated from their children.

Mathieson's and the Belgian brothers' adoption papers do not describe any effort to locate their families, despite the many years spent in the orphanage system.

Mathieson claims she is filled with questions. Did her parents abandon her with a relative living in Busan, while she searched for their missing sons' remains? Did she get kidnapped like other Brothers inmates?

Mathieson stated that "a lot of the adoptions were from new parents who had to give up their child immediately after birth." Mathieson said that it was possible for a family to surrender, voluntarily surrender, three children between the ages 4 and 6. It didn't make sense to me. I knew the truth of the story was so deep."

The AP obtained documents from lawmakers, officials and freedom-of-information requests and found direct evidence that 19 children were adopted by Brothers between 1979-1986. Indirect evidence suggests at least 51 additional adoptions.

Mathieson's childhood memories of Korea, where she watched children play in an empty outdoor pool and had to climb over black iron gates to see the flowers, were vague and benign. She was hurriedly taking photographs in a courtyard garden when she was told by the AP that she'd been at Brothers.

Now, she connects those photos with Brothers photos of children playing in low water in a concrete pit behind massive barred gates. This was before a prosecutor exposed its horrors in 1987.

Brothers was the largest facility that housed the military's aggressive roundups. Adoptions were another method to eliminate the socially unattractive, such as children from unwed mothers and poor families, and reduce the number hungry.

In the last six decades, approximately 200,000 Korean children have been adopted by West families. This includes 7,924 in 1984 when Mathieson was adopted. Many of the children who were adopted by families in the West are difficult to trace because they were often listed as abandoned.

Mathieson will present her case to Seoul’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This commission has interviewed hundreds of Brothers survivors and their families but no adoptees. Mathieson is determined to find out more about her biological parents but she treasures the bits of her past as she continues her search.

Mathieson stated that it was great to receive additional photos from Korea Welfare Service, her agency for adoption. They will be treasured forever."