Jewelry has long been recognized as a powerful symbol of love and commitment. This article delves into the various dimensions of jewelry as a cherished gift, exploring its cultural, emotional, and historical significance. By understanding these aspects, we can appreciate why jewelry continues to be a beloved token of affection around the world.

Jewelry has transcended generations, embodying deep emotions and personal connections. Its allure lies in the ability to convey feelings that words often cannot express. From exquisite necklaces to delicate bracelets, each piece tells a unique story of love.

Across the globe, different cultures have rich traditions surrounding jewelry as a symbol of love. Understanding these cultural nuances enhances our appreciation for the role jewelry plays in expressing affection.

In Western cultures, the engagement ring is a profound symbol of commitment. This tradition has evolved, reflecting changing societal values and personal beliefs about relationships.

The practice of giving engagement rings dates back to ancient Rome, where they signified a formal agreement between partners. Today, these rings carry even greater emotional weight, often representing a promise of lifelong love.

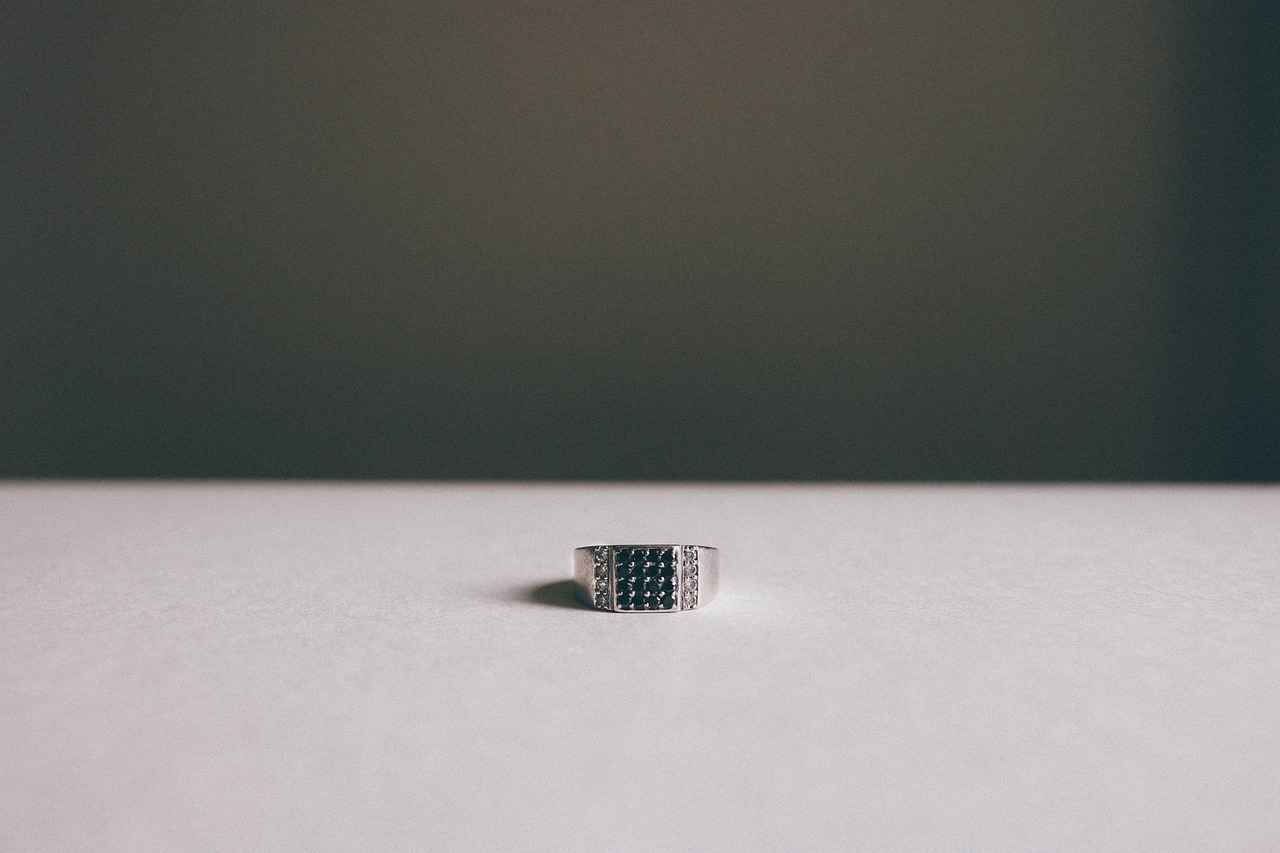

Contemporary trends showcase a variety of styles, from vintage designs to modern minimalism, allowing couples to express their unique love stories through their choice of rings.

In many Eastern cultures, jewelry is intricately linked with customs and rituals. For instance, in Indian weddings, gold jewelry is a symbol of prosperity and marital bliss, highlighting the cultural significance of these adornments.

Jewelry often carries sentimental value, representing cherished memories and milestones in relationships. This emotional connection enhances its significance as a symbol of love.

Heirloom pieces passed down through generations hold deep emotional significance, serving as tangible reminders of love, family history, and shared experiences.

Custom-made jewelry, such as engraved pieces, allows individuals to express their feelings uniquely, making the gift even more special and memorable.

The choice of jewelry often reflects personal tastes and relationship dynamics. Understanding these preferences can provide insight into the meaning behind the gift.

Various gemstones carry specific meanings and are often chosen for their symbolic significance in love and relationships, adding depth to the gift. For example, diamonds symbolize eternal love, while emeralds represent rebirth and hope.

The type of metal used in jewelry, such as gold or silver, can also convey different messages about love, commitment, and personal style. Gold is often associated with wealth and permanence, while silver can symbolize purity and clarity.

Giving jewelry can strengthen emotional bonds in relationships, serving as a physical manifestation of love and commitment that enhances intimacy.

Jewelry often marks significant life events, such as anniversaries or birthdays, reinforcing the importance of these occasions in a relationship.

The act of presenting jewelry is often accompanied by rituals or traditions that deepen the emotional impact of the gift, creating lasting memories.

The jewelry industry employs various marketing strategies to position jewelry as the ultimate symbol of love, influencing consumer perceptions and behaviors.

Many brands create compelling narratives around love and commitment in their advertising, shaping how consumers view jewelry as a gift. These campaigns often highlight the emotional journey associated with giving and receiving jewelry.

Social media platforms play a significant role in promoting jewelry trends, impacting how people perceive and choose jewelry as symbols of love. Influencers often showcase unique pieces, making them desirable gifts.

Selecting the right piece of jewelry requires careful consideration of personal preferences, occasions, and the message you wish to convey through the gift.

Knowing your partner’s taste is crucial in choosing jewelry that resonates with them, ensuring that the gift feels personal and meaningful.

Setting a budget can help narrow down choices while still allowing for a thoughtful and heartfelt gift that symbolizes your love.

What Makes Jewelry a Timeless Gift?

Jewelry has long been revered as a cherished gift, transcending time and culture. Its significance as a symbol of love and commitment is deeply rooted in human history. The unique ability of jewelry to convey emotions makes it a timeless choice for expressing affection, making it a favored gift for countless occasions.

Jewelry has been a favored gift for centuries, symbolizing love and commitment. Its enduring appeal lies in its ability to convey deep emotions and personal connections. The act of giving jewelry often marks significant milestones in relationships, such as engagements, anniversaries, or birthdays, reinforcing the bond between partners.

- Emotional Resonance: Jewelry often carries sentimental value, serving as a tangible reminder of special moments shared between loved ones.

- Universal Symbolism: Across cultures, jewelry embodies various meanings and traditions, enhancing its significance as a gift.

- Personalization: Custom-made pieces allow individuals to express their feelings in unique ways, making the gift more meaningful.

Different cultures have unique traditions surrounding jewelry as a love token. Understanding these cultural nuances can enhance our appreciation for jewelry’s role in expressing affection. For example, in Western cultures, engagement rings symbolize commitment, while in Eastern cultures, jewelry often plays a crucial role in weddings and ceremonies.

Jewelry often carries a profound emotional significance, representing cherished memories and milestones in relationships. Heirloom pieces passed down through generations often hold deep emotional weight, serving as tangible reminders of love and family history. Additionally, personalized jewelry, such as engraved pieces, allows individuals to express their feelings in a unique way, making the gift even more special and memorable.

The choice of jewelry often reflects personal tastes and relationship dynamics. For instance, various gemstones carry specific meanings and are often chosen for their symbolic significance in love and relationships. Understanding the symbolism behind different gemstones can add depth to the gift, making it more meaningful.

Giving jewelry can strengthen emotional bonds in relationships, serving as a physical manifestation of love and commitment. Jewelry often marks significant life events, such as anniversaries or birthdays, reinforcing the importance of these occasions in a relationship. The act of presenting jewelry is often accompanied by rituals or traditions that deepen the emotional impact of the gift, creating lasting memories.

Selecting the right piece of jewelry requires careful consideration of personal preferences, occasions, and the message you wish to convey through the gift. Understanding your partner’s style is crucial in choosing jewelry that resonates with them, ensuring that the gift feels personal and meaningful. Additionally, setting a budget can help narrow down choices while still allowing for a thoughtful and heartfelt gift that symbolizes your love.

How Does Jewelry Represent Love Across Cultures?

Jewelry has long been a cherished gift, transcending borders and cultures to symbolize love and commitment. Understanding how different cultures perceive and utilize jewelry as a token of affection not only enriches our appreciation for these adornments but also highlights the diverse ways in which love is expressed globally.

Across various cultures, jewelry is not merely an accessory; it holds deep cultural significance. In many societies, jewelry is used in rituals, celebrations, and as a representation of love and devotion.

In Western societies, the engagement ring is a powerful symbol of love and commitment. Traditionally, these rings are made of precious metals and adorned with diamonds, which represent eternity. The practice of giving engagement rings dates back to ancient Rome, where they signified a formal agreement between partners. Today, they carry a deeper emotional weight, reflecting personal stories and shared journeys.

In many Eastern cultures, jewelry is intricately linked with customs and traditions. For instance, in India, gold jewelry is considered auspicious and is often given during weddings and festivals. The jewelry worn by brides is rich in symbolism, representing prosperity and the strength of the marital bond. Similarly, in Chinese culture, jade is highly valued and often gifted as a token of love and protection.

Understanding the specific customs surrounding jewelry can enhance our appreciation for its role in expressing affection. For example, in some African cultures, intricate beadwork is not just decorative but tells a story of the wearer’s heritage and relationships. In contrast, Western preferences might lean towards minimalist designs that emphasize personal style and sentiment.

Jewelry often marks significant life events, such as anniversaries, weddings, or births, reinforcing the importance of these occasions. In many cultures, gifting jewelry can symbolize a promise, commitment, or a milestone in a relationship. For instance, a couple might exchange matching bracelets to signify their bond, while others may choose to gift heirloom pieces passed down through generations, serving as tangible reminders of love and family history.

Jewelry often carries sentimental value, representing cherished memories and milestones in relationships. Heirloom pieces, for example, hold deep emotional significance, connecting individuals to their family history and past loves. Personalized jewelry, such as engraved rings or pendants, allows individuals to express their feelings uniquely, making the gift even more special and memorable.

The choice of jewelry reflects personal tastes and relationship dynamics. Different gemstones carry specific meanings; for example, sapphires symbolize wisdom and loyalty, while rubies represent passion and love. Understanding these meanings can add depth to the gift, making it more meaningful for the recipient.

The jewelry industry employs various marketing strategies to position jewelry as the ultimate symbol of love. Compelling narratives around love and commitment are crafted in advertising campaigns, shaping how consumers perceive jewelry as a gift. Social media platforms also play a significant role in promoting trends, influencing how people choose jewelry to symbolize their affection.

In conclusion, jewelry serves as a universal language of love, transcending cultural boundaries. By exploring the rich traditions and meanings associated with jewelry across different cultures, we gain a deeper appreciation for its role in expressing affection and commitment.

Western Traditions and Engagement Rings

In Western cultures, the tradition of giving engagement rings has become a powerful symbol of love and commitment. This practice has undergone significant transformations over the years, adapting to reflect changing societal norms and personal values associated with romantic relationships. Understanding the history and significance of engagement rings can provide deeper insights into why they are cherished tokens of affection.

The custom of presenting engagement rings can be traced back to ancient Rome, where rings were exchanged as a formal agreement between partners. Initially, these rings were simple bands made of iron, symbolizing strength and permanence. Over time, the materials and designs evolved, reflecting the wealth and status of the giver.

In the 20th century, the marketing of diamonds transformed the engagement ring landscape. The famous slogan, “A diamond is forever,” popularized the idea that diamonds represent eternal love. This marketing campaign significantly influenced consumer perceptions, leading many to associate diamonds with commitment and exclusivity.

Today, couples are increasingly opting for personalized engagement rings that reflect their unique love stories. From vintage styles to contemporary designs, the options are limitless. Many choose non-traditional gemstones or custom settings, allowing for a more individualized expression of their commitment. This shift highlights a growing trend towards authenticity and personal connection in relationships.

While Western cultures have popularized the diamond engagement ring, other cultures have their own unique traditions. For instance, in some Eastern cultures, engagement rings may not be as prevalent, with other forms of jewelry or gifts symbolizing commitment. Understanding these diverse traditions enriches our appreciation for the role of jewelry in expressing love across different societies.

Engagement rings often carry profound emotional significance, serving as tangible reminders of a couple’s commitment to one another. They mark a pivotal moment in a relationship, encapsulating the love and promises exchanged. This emotional connection is what makes the act of giving an engagement ring so meaningful.

Selecting the right engagement ring requires careful consideration of various factors:

- Understanding Your Partner’s Style: Pay attention to their jewelry preferences and lifestyle to choose a ring that resonates with them.

- Setting a Budget: Determine a budget that allows for a thoughtful purchase without financial strain.

- Choosing the Right Gemstone: Consider the symbolism of different gemstones and their significance in your relationship.

The jewelry industry employs various marketing strategies to position engagement rings as essential symbols of love. Advertising campaigns often create romantic narratives that resonate with consumers, shaping their perceptions of what an engagement ring should represent. Additionally, social media platforms have become influential in showcasing trends, impacting how couples choose their rings.

In conclusion, engagement rings are more than just pieces of jewelry; they are powerful symbols of love, commitment, and personal values. As traditions continue to evolve, the significance of these rings remains rooted in the deep emotional connections they represent.

Origin of the Engagement Ring

The tradition of giving engagement rings is a practice steeped in history, with roots tracing back to ancient civilizations. Engagement rings have evolved significantly over the centuries, reflecting not only personal sentiments but also cultural values and societal norms.

The custom of presenting an engagement ring began in ancient Rome, where it symbolized a formal agreement between partners. Roman brides were given rings made of iron, which represented strength and permanence in their commitment. This practice was not merely a token of affection but a public declaration of intent, solidifying the bond between two individuals.

Today, engagement rings carry a much deeper emotional weight. They represent not only the promise of marriage but also the love, devotion, and aspirations that couples share. The ring serves as a constant reminder of the commitment made between partners, symbolizing their journey together.

Over the centuries, the design and materials of engagement rings have transformed dramatically. In the Middle Ages, rings often featured intricate designs and were adorned with gemstones that were believed to possess protective qualities. By the 19th century, the introduction of diamond engagement rings, popularized by the famous phrase “A diamond is forever,” further solidified the diamond’s status as the ultimate symbol of love and commitment.

In contemporary society, engagement rings have become highly personalized. Couples now have the freedom to choose from a wide array of styles, materials, and gemstones. From vintage-inspired designs to minimalist settings, the options are endless. Many couples opt for custom-made rings that reflect their unique love stories, incorporating personal touches such as engraved messages or birthstones.

The emotional significance of engagement rings cannot be overstated. They often mark a pivotal moment in a couple’s relationship, serving as a tangible representation of their love and commitment. The act of choosing or designing an engagement ring can also be a deeply personal experience, allowing partners to express their feelings and intentions in a meaningful way.

Across the globe, different cultures have their own unique traditions surrounding engagement rings. In some cultures, the engagement ring is worn on the right hand, while in others, it is placed on the left. Additionally, certain cultures may incorporate specific symbols or materials that hold particular significance, further enhancing the meaning behind the ring.

When selecting an engagement ring, it is essential to consider your partner’s style and preferences. Understanding their taste in jewelry can guide you in choosing a piece that resonates with them. Additionally, budgeting is crucial; engagement rings come in various price ranges, allowing for thoughtful choices that still convey deep affection.

In summary, the engagement ring is more than just a piece of jewelry; it embodies the love and commitment shared between partners. As this tradition continues to evolve, it remains a cherished symbol of romance and devotion.

Modern Trends in Engagement Rings

reflect the evolving tastes and preferences of couples today. As love stories become more personalized, the choice of engagement rings has transformed into a unique expression of each couple’s journey. This article delves into the contemporary styles and personalization options available, highlighting how couples can showcase their individuality through their ring selections.

Today’s engagement rings come in a myriad of styles that cater to diverse tastes. From classic solitaires to intricate vintage designs, the options are endless. Couples can choose from minimalistic styles that emphasize simplicity and elegance, or opt for bold statement pieces that make a unique impression. The rise of alternative gemstones, such as sapphires and emeralds, has also gained popularity, allowing couples to break away from the traditional diamond.

Personalization has become a significant trend in the world of engagement rings. Couples are increasingly seeking ways to make their rings reflect their personal stories and values. Customization options include:

- Engraving: Adding a special date or message inside the band can make the ring even more meaningful.

- Choosing Unique Settings: Selecting a distinctive setting can set a ring apart, such as a halo or a three-stone arrangement.

- Mixing Metals: Combining different metal types, like gold and rose gold, can create a striking visual effect.

As societal norms shift, many couples are opting for non-traditional engagement rings that reflect their personal style rather than adhering to conventional standards. This trend is fueled by a desire for authenticity and a rejection of traditional expectations. Couples are embracing rings that resonate with their lifestyle and values, making a strong statement about their relationship.

In recent years, there has been a growing awareness of ethical sourcing in the jewelry industry. Many couples are now prioritizing conflict-free diamonds or opting for lab-created stones, which are often more affordable and environmentally friendly. This shift reflects a broader commitment to sustainability and ethical consumption, allowing couples to choose rings that align with their values.

Social media platforms like Instagram and Pinterest have become influential in shaping engagement ring trends. Couples often turn to these platforms for inspiration, discovering new styles, gemstones, and customization ideas. Influencers and celebrities showcase their unique rings, setting trends that resonate with their followers. This exposure has led to a more informed consumer base that actively seeks out distinctive and personalized options.

Selecting the perfect engagement ring can be daunting, but considering a few key factors can simplify the process:

- Know Your Partner’s Style: Pay attention to the jewelry they currently wear to gauge their preferences.

- Consider Lifestyle: Choose a ring that complements your partner’s daily activities and lifestyle.

- Set a Budget: Determine a budget that allows for a meaningful purchase without financial strain.

In conclusion, modern trends in engagement rings celebrate individuality and personal expression. With an array of styles and personalization options, couples can find the perfect ring that tells their unique love story. As the jewelry market continues to evolve, the focus on ethical choices and innovative designs will likely shape the future of engagement rings even further.

Eastern Perspectives on Jewelry and Love

In many Eastern cultures, jewelry holds a profound significance that goes beyond mere adornment. It is often deeply intertwined with customs, rituals, and the very fabric of social interactions. Understanding these cultural perspectives can illuminate the vital role jewelry plays in romantic relationships, revealing layers of meaning that are often overlooked in Western contexts.

In Eastern traditions, jewelry is not just a fashion statement; it is a symbol of status, wealth, and commitment. For instance, in countries like India, jewelry is an integral part of wedding ceremonies, where it is customary for brides to wear elaborate pieces that signify their new role within the family. These pieces, often adorned with precious stones, are seen as a blessing and a means of securing a prosperous future.

Jewelry in Eastern cultures is often accompanied by specific rituals that enhance its significance. For example, during traditional Chinese weddings, the bride may receive a gold necklace from her parents, symbolizing their love and support. This act is not merely about the jewelry itself; it represents the continuity of family and cultural heritage, signifying that the bride is cherished and will carry forward these values.

The choice of materials in jewelry also carries deep meaning. In many Eastern cultures, gold is preferred for its durability and value, representing a lasting commitment. Silver, on the other hand, may symbolize purity and clarity of intention. The specific choice of metal or gemstone can convey messages about the relationship, reflecting the couple’s unique dynamics and shared values.

Jewelry often serves as a bridge between generations, with heirloom pieces passed down as symbols of love and family history. In many cultures, these heirlooms are imbued with stories and memories, creating a tangible connection to the past. For example, a grandmother’s ring may be given to a granddaughter as a token of love and continuity, reinforcing family bonds and shared experiences.

In Eastern cultures, gifting jewelry is often laden with emotional significance. It is common for individuals to present jewelry during significant life events, such as engagements or anniversaries, reinforcing the emotional ties that bind couples together. This act of giving not only strengthens the relationship but also serves as a public declaration of love and commitment.

As globalization continues to shape cultural practices, modern trends are influencing traditional jewelry customs in Eastern societies. The rise of personalized jewelry, such as engraved pieces, allows couples to express their individuality while still honoring cultural traditions. This fusion of modernity and tradition reflects the evolving nature of relationships and the ways in which love is expressed through jewelry.

In summary, jewelry in Eastern cultures transcends its aesthetic appeal, embodying deep cultural meanings, emotional connections, and familial ties. By understanding these perspectives, we can appreciate the profound significance of jewelry in romantic relationships, recognizing it as a powerful symbol of love that resonates across generations.

What Are the Emotional Connections to Jewelry?

Jewelry serves as more than just an accessory; it embodies profound emotional connections that resonate deeply with individuals. The act of giving or receiving jewelry often transcends its physical form, becoming a vessel for cherished memories and significant milestones in relationships. This article delves into the emotional connections associated with jewelry, exploring how it symbolizes love and personal history.

For many, jewelry is imbued with sentimental value, representing pivotal moments in life. A piece of jewelry can encapsulate the essence of a relationship, serving as a reminder of shared experiences and emotions. Whether it’s a necklace gifted on a birthday or a pair of earrings received on an anniversary, these items often carry stories that enhance their significance.

Heirloom jewelry is a prime example of how jewelry can forge emotional connections across generations. Passed down from grandparents to parents, and then to children, these pieces often symbolize enduring love and familial ties. Each heirloom carries its own history, reminding the wearer of their roots and the love that has been shared within the family.

Custom-made jewelry, such as engraved pieces or birthstone settings, allows individuals to express their feelings in a unique way. Personalized jewelry transforms a simple gift into a heartfelt token, making it even more special. The act of personalizing a piece signifies thoughtfulness and effort, deepening the emotional connection between the giver and the recipient.

Jewelry often marks significant life events, such as engagements, weddings, and anniversaries. Each piece can represent a milestone in a relationship, reinforcing the importance of these occasions. For instance, an engagement ring symbolizes a commitment to a future together, while a wedding band serves as a daily reminder of that promise.

The act of presenting jewelry is frequently accompanied by rituals or traditions that enhance its emotional impact. Whether it’s a proposal, a birthday celebration, or a holiday gathering, the context in which jewelry is given can create lasting memories. These rituals often involve heartfelt speeches or intimate moments, making the gift even more meaningful.

Personal experiences significantly shape how individuals perceive and choose jewelry. For some, a particular style or gemstone may evoke memories of a loved one, while others might prefer pieces that reflect their personal journey. Understanding these preferences can provide insight into the emotional significance behind each piece of jewelry.

Jewelry can also play a role in emotional healing. For individuals going through difficult times, wearing a piece of jewelry that symbolizes strength or resilience can serve as a source of comfort. This connection can help individuals navigate through their emotions, reminding them of their inner strength and the love that surrounds them.

Cultural backgrounds can influence the emotional connections people have with jewelry. Different cultures have unique traditions surrounding the gifting of jewelry, often associating specific pieces with love and commitment. Understanding these cultural nuances can enhance our appreciation for jewelry’s role in expressing affection.

In conclusion, jewelry is much more than a decorative item; it is a profound symbol of love, history, and emotional connection. Whether through heirlooms, personalized gifts, or significant milestones, jewelry continues to hold a special place in our hearts, reminding us of the relationships and memories that shape our lives.

Sentimental Value of Heirloom Jewelry

is a topic that resonates deeply with many individuals. Heirloom pieces, which are often passed down through generations, carry with them a rich tapestry of emotional significance and familial history. These treasured items serve not only as beautiful adornments but also as tangible reminders of love, resilience, and the stories of those who came before us.

When we think of heirloom jewelry, we often envision ornate pieces that have been lovingly cared for over the years. Each piece tells a story, whether it’s a grandmother’s delicate locket or a mother’s engagement ring. The emotional weight of these items is profound, as they connect us to our ancestors and remind us of the bonds that unite families. For many, wearing these pieces is akin to carrying a piece of their loved ones with them, fostering a sense of closeness even when physically apart.

Moreover, heirloom jewelry often marks significant milestones in a family’s history. For example, a wedding band passed from mother to daughter symbolizes not only the continuity of love but also the values and traditions that have shaped a family over generations. Each time the piece is worn, it evokes memories and emotions associated with the previous owner, reinforcing the legacy of love that transcends time.

The craftsmanship of heirloom jewelry also adds to its sentimental value. Many heirloom pieces are handmade, showcasing the skill and artistry of the jeweler. This unique quality often makes heirloom jewelry more special than contemporary pieces, as they embody the time and care invested in their creation. Additionally, the materials used in these pieces often have their own stories, whether it be a rare gemstone sourced from a far-off land or a particular metal that has been cherished for its durability and beauty.

In many cultures, the act of passing down jewelry is steeped in tradition. This practice not only preserves the physical item but also the stories and values associated with it. For instance, in some cultures, it is common for mothers to pass down their wedding rings to their daughters, symbolizing the continuity of love and commitment through generations. Such rituals reinforce the idea that love is not just a fleeting emotion, but a legacy to be cherished and honored.

Furthermore, the personalization of heirloom jewelry enhances its sentimental value. Many families choose to modify or engrave heirloom pieces to reflect their personal stories. This customization can make the jewelry even more meaningful, as it incorporates the individual’s journey while still honoring the past. For example, adding initials or significant dates can transform a simple piece into a cherished family heirloom, bridging the gap between generations.

In conclusion, the sentimental value of heirloom jewelry lies in its ability to connect us to our past while celebrating our present. These pieces are more than just accessories; they are living artifacts that carry the love, memories, and stories of our ancestors. As we wear and cherish these items, we honor the legacy of those who came before us, ensuring that their stories continue to be told through the generations.

Personalized Jewelry as a Love Token

When it comes to expressing love and affection, jewelry has long been cherished as a meaningful gift. Among the various types of jewelry, personalized pieces hold a special place in the hearts of many. These custom-made items, such as engraved necklaces or bracelets, allow individuals to express their emotions in a unique and profound way, making the act of gifting even more memorable.

Personalized jewelry stands out because it transforms a simple piece into a symbol of love. By adding names, initials, or significant dates, the jewelry becomes a reflection of the relationship, encapsulating shared memories and milestones. This level of customization fosters a deeper emotional connection between the giver and the recipient.

- Uniqueness: Engraved pieces are one-of-a-kind, ensuring that the gift is unlike anything else.

- Sentimental Value: Personal touches make the jewelry more meaningful and memorable.

- Versatility: Personalized jewelry can be tailored for any occasion, whether it’s a birthday, anniversary, or just because.

The act of giving personalized jewelry often creates a lasting bond between partners. When someone receives a piece that has been thoughtfully customized, it serves as a constant reminder of the love and effort put into selecting the gift. This emotional connection can strengthen relationships, making the jewelry not just an accessory but a cherished keepsake.

There are various forms of personalized jewelry that individuals can choose from:

- Engraved Necklaces: A popular choice for couples, often featuring names or special dates.

- Customized Bracelets: These can include charms or engravings that symbolize significant moments in the relationship.

- Rings: Engraved rings can serve as a reminder of love, commitment, or friendship.

Choosing the right piece of personalized jewelry requires thoughtful consideration:

- Know Their Style: Understanding your partner’s taste is crucial. Consider their favorite metals, colors, and styles.

- Significant Symbols: Think about symbols or words that hold special meaning in your relationship.

- Occasion: Tailor the piece to the occasion, ensuring it resonates with the moment being celebrated.

Many jewelers offer customization services, but it’s essential to choose a reputable source. Look for:

- Customer Reviews: Check feedback from previous customers to gauge quality and service.

- Material Quality: Ensure that the materials used are durable and of high quality.

- Design Options: A good jeweler should provide various customization options to suit your needs.

In conclusion, personalized jewelry serves as a profound love token that encapsulates feelings and memories. Its unique nature and emotional significance make it an ideal gift for any occasion. By choosing personalized jewelry, individuals can create lasting connections and celebrate their love in a truly special way.

Why Do People Choose Specific Types of Jewelry?

Jewelry has long been a cherished gift, often representing significant moments in relationships. The choice of specific types of jewelry can reveal much about personal tastes and the dynamics of relationships. Understanding these preferences not only enhances the appreciation for the gift but also provides insights into the giver’s intentions and the recipient’s personality.

When selecting jewelry, various factors come into play, including personal style, cultural significance, and emotional connections. Each piece carries its own story, and the decision to choose one type over another often reflects deeper meanings.

- Classic vs. Modern: Some individuals gravitate towards timeless designs, such as diamond stud earrings or simple gold bands, while others prefer contemporary styles that showcase unique designs and materials.

- Color Preferences: The choice of metal—gold, silver, or platinum—can indicate personal taste. Additionally, some may favor colorful gemstones, which can reflect their personality or birth month.

Each gemstone carries its own symbolism and meaning, which often influences the choice of jewelry:

- Diamonds: Often associated with love and eternity, diamonds are a popular choice for engagement rings.

- Rubies: Symbolizing passion and desire, rubies can signify a deep emotional connection.

- Sapphires: Representing loyalty and trust, sapphires are frequently chosen for wedding bands.

The metal used in jewelry can also convey different messages. For instance:

- Gold: Often associated with wealth and success, gold jewelry can symbolize prosperity in a relationship.

- Silver: Known for its versatility, silver may represent purity and clarity of intention.

- Platinum: A rare and durable metal, platinum jewelry signifies a lasting commitment.

The choice of jewelry can also reflect the dynamics within a relationship. For example:

- Romantic Relationships: Couples often choose pieces that symbolize their love, such as matching bracelets or personalized necklaces.

- Friendship: Friendship bracelets or charms can signify a bond that goes beyond romantic love, representing loyalty and support.

- Family Connections: Heirloom jewelry passed down through generations often holds sentimental value, serving as a reminder of family history and legacy.

Jewelry often carries a sentimental value that enhances its meaning. For instance, a piece of jewelry given on a significant occasion, such as an anniversary or birthday, can evoke cherished memories and feelings. Custom-made jewelry, such as engraved pieces, allows individuals to express their feelings uniquely, making the gift even more special and memorable.

In recent years, trends have emerged that influence how people choose jewelry. The rise of sustainable and ethically sourced materials has led many to seek out pieces that align with their values. Furthermore, social media platforms have played a crucial role in shaping jewelry trends, showcasing styles that resonate with younger generations.

In conclusion, the choice of jewelry is a multifaceted decision influenced by personal taste, symbolism, and relationship dynamics. Understanding these factors can provide valuable insights into the meaning behind the gift, enriching the emotional experience for both the giver and the recipient.

Symbolism of Different Gemstones

When it comes to expressing love and commitment, gemstones have long been revered for their unique meanings and symbolic significance. Each gemstone carries its own story, often reflecting emotions, intentions, and desires. This article delves into the and how they can enhance the depth of a gift, particularly in the context of love and relationships.

Gemstones have been associated with various emotions and attributes throughout history. Their symbolic meanings can add a profound layer to the act of giving jewelry. For example, many people choose specific gemstones based on their meanings, aligning them with the sentiments they wish to convey.

- Diamonds: Often regarded as the ultimate symbol of love, diamonds signify eternity and commitment. Their durability and brilliance make them a popular choice for engagement rings.

- Ruby: Known for its deep red hue, rubies symbolize passion and desire. They are often given to express deep romantic feelings.

- Sapphire: Traditionally associated with wisdom and loyalty, sapphires are often chosen to represent a steadfast and enduring love.

- Emerald: With its vibrant green color, emeralds symbolize rebirth and growth, making them an excellent choice for couples looking to nurture their relationship.

- Amethyst: Known for its calming properties, amethyst represents tranquility and spirituality. It is often given to promote harmony in relationships.

Selecting a gemstone that resonates with your partner’s personality and your relationship can make the gift even more special. Consider the following:

- Reflect on their personal style and preferences. Do they prefer bold and vibrant colors, or are they drawn to more subtle hues?

- Think about the message you want to convey. Are you celebrating a milestone, or simply wanting to express your feelings?

- Research the meanings associated with different gemstones to find one that aligns with your sentiments.

Many gemstones are linked to specific months and are referred to as birthstones. These stones not only carry their own meanings but also have cultural significance. For example:

- January: Garnet, symbolizing protection and strength.

- February: Amethyst, known for promoting calm and balance.

- March: Aquamarine, representing serenity and clarity.

- April: Diamond, symbolizing eternal love.

By gifting a birthstone, you not only acknowledge the recipient’s birth month but also incorporate a personal touch that enhances the emotional value of the gift.

Many couples opt for custom jewelry that incorporates specific gemstones to create a unique piece that tells their love story. This personalization allows for:

- Enhanced emotional significance, as the gemstone can symbolize a shared experience or memory.

- The opportunity to mix and match different stones to represent various aspects of the relationship.

- A creative way to express individuality while celebrating the bond between partners.

In conclusion, the symbolism of different gemstones can greatly enhance the meaning of jewelry gifts. By understanding the significance behind each stone, individuals can choose pieces that resonate deeply with their emotions and intentions, making their expressions of love even more profound.

Choosing Metal Types for Meaning

When it comes to selecting jewelry, the type of metal chosen plays a crucial role in conveying messages about love, commitment, and personal style. Each metal carries its own symbolism and cultural significance, making the choice of metal a deeply personal decision.

Different metals are often associated with varying emotions and values:

- Gold: Often seen as a symbol of wealth and prosperity, gold is also linked to eternal love due to its durability and timeless appeal. It is a popular choice for engagement rings and wedding bands, representing a commitment that lasts a lifetime.

- Silver: This metal embodies purity and clarity, often chosen for its elegant appearance and affordability. Silver jewelry can signify a gentle love and is frequently used in gifts for anniversaries and special occasions.

- Platinum: Known for its rarity and strength, platinum symbolizes unconditional love. It is hypoallergenic and resistant to tarnish, making it a perfect choice for those with sensitive skin.

- Rose Gold: This trendy metal blends gold with copper, giving it a warm, romantic hue. Rose gold has become increasingly popular for its unique aesthetic, representing affection and romance.

The choice of metal in jewelry not only reflects the wearer’s personality but also their relationship dynamics. For instance, someone who prefers classic styles might gravitate towards gold or platinum, while a more eclectic individual may choose silver or rose gold. Additionally, the metal can complement the gemstone selection, enhancing the overall aesthetic of the piece.

In many cultures, the type of metal used in jewelry carries significant meaning. For example:

- In some Eastern cultures, gold is not just a precious metal but is also viewed as a harbinger of good fortune and prosperity in marriage.

- In Western traditions, the choice of metal for engagement rings often follows trends, but it also reflects the couple’s values and lifestyle.

When selecting jewelry, consider the following factors:

- Personal Preference: Think about the recipient’s style and preferences. Do they prefer classic or modern designs? Are they sensitive to certain metals?

- Occasion: The occasion can dictate the type of metal. For instance, gold may be more suitable for significant events like engagements, while silver might be perfect for casual gifts.

- Longevity: Consider how often the jewelry will be worn. Metals like platinum and gold are more durable and suitable for everyday wear.

Ultimately, the choice of metal is a reflection of personal taste and the sentiments you wish to convey. By understanding the meanings behind different metals, you can select a piece that truly resonates with the recipient, making it a cherished symbol of your love.

How Do Jewelry Gifts Enhance Romantic Relationships?

Jewelry has long been regarded as a powerful symbol of love and commitment, transcending cultural boundaries and historical contexts. The act of giving jewelry serves not only as a tangible representation of affection but also plays a significant role in enhancing emotional bonds between partners. In this section, we will explore how jewelry gifts can strengthen romantic relationships and foster deeper connections.

The significance of jewelry in romantic relationships stems from its ability to convey deep emotions and personal sentiments. When a partner presents a piece of jewelry, it often symbolizes their dedication and commitment to the relationship. This physical manifestation of love can enhance intimacy, as it serves as a lasting reminder of shared experiences and promises made.

Jewelry is often given to commemorate important milestones in a relationship, such as anniversaries, engagements, or birthdays. These gifts help to reinforce the significance of these occasions, making them memorable and special. For instance, a couple celebrating their fifth anniversary may choose to exchange diamond jewelry, which symbolizes the strength and durability of their love.

Jewelry often carries a sentimental value that goes beyond its aesthetic appeal. Many couples cherish heirloom pieces that have been passed down through generations, serving as tangible reminders of family history and love. These heirlooms can evoke powerful emotions, reminding partners of their shared journey and the legacy of love that surrounds them.

The act of giving jewelry is frequently accompanied by rituals or traditions that deepen its emotional impact. For example, a surprise proposal with a carefully chosen ring can create a moment of profound significance, strengthening the bond between partners. Such rituals not only enhance the experience but also create lasting memories that couples can cherish for years to come.

Personalized jewelry, such as engraved pieces or custom designs, allows individuals to express their feelings in a unique way. This personal touch adds an extra layer of meaning to the gift, making it even more special. By incorporating personal elements, such as initials or significant dates, couples can create a symbol of their love that is truly one-of-a-kind.

Different types of jewelry can convey various messages about love and commitment. For instance, a simple necklace may represent a more casual relationship, while a diamond ring signifies a serious commitment. Understanding the symbolism behind different jewelry types can help partners choose gifts that reflect their relationship dynamics and intentions.

- Strengthens emotional bonds: Jewelry serves as a physical reminder of love and commitment.

- Enhances intimacy: The act of giving jewelry can create moments of closeness and connection.

- Commemorates milestones: Jewelry marks significant events, reinforcing the importance of shared experiences.

- Creates lasting memories: The rituals surrounding jewelry gifts can create cherished memories.

In summary, jewelry gifts play a vital role in enhancing romantic relationships by serving as symbols of love, commitment, and shared experiences. By understanding the emotional significance of these gifts, couples can deepen their connections and celebrate their love in meaningful ways.

Jewelry as a Celebration of Milestones

Jewelry has long been recognized as a powerful symbol of love and commitment, often marking significant milestones in our lives. From birthdays to anniversaries, the act of giving jewelry during these pivotal moments reinforces the emotional bonds shared between partners. But what makes jewelry such a cherished gift during these occasions?

Milestones are important markers in our lives, representing growth, achievement, and shared experiences. When we choose to commemorate these moments with jewelry, we are not just giving a physical object; we are offering a lasting reminder of love and connection. This practice is deeply rooted in cultural traditions that vary across the globe.

Each piece of jewelry carries a unique story that can evoke memories of special occasions. For example, a diamond necklace may symbolize a couple’s first anniversary, while a birthstone ring can represent the birth of a child. These tangible items serve as reminders of the love and joy experienced during these significant events.

- Western Cultures: In many Western societies, it is common to give jewelry during anniversaries, particularly the first, fifth, and tenth. Each year often has a traditional gemstone associated with it, adding layers of meaning to the gift.

- Eastern Traditions: In Eastern cultures, jewelry is often integral to celebrations such as weddings and births. Gold, for instance, is a popular choice as it symbolizes prosperity and good fortune.

Giving jewelry during significant life events can create a profound emotional impact. It serves as a physical manifestation of love, making the moment even more memorable. A carefully chosen piece can express feelings that words sometimes cannot, deepening the emotional connection between partners.

Personalization is a growing trend in the jewelry industry. Custom-made pieces allow individuals to engrave names, dates, or special messages, making the gift even more meaningful. This level of thoughtfulness can transform a simple piece of jewelry into a treasured heirloom, passed down through generations.

As relationships evolve, so do the milestones we celebrate. Jewelry acts as a tangible reminder of the journey partners have taken together. Whether it’s a charm bracelet that grows with each new experience or a matching set of rings to symbolize unity, these gifts can enhance intimacy and reinforce commitment.

In conclusion, jewelry is much more than just an adornment; it is a powerful symbol of love and a celebration of life’s milestones. By understanding the significance of these gifts, we can appreciate the emotional connections they foster and the memories they help create. Whether it’s a simple pendant or an elaborate piece, jewelry remains a timeless way to honor the special moments in our lives.

The Ritual of Giving Jewelry

The act of giving jewelry is steeped in tradition and emotion, transforming a simple gift into a profound expression of love and commitment. Across various cultures, the presentation of jewelry is often accompanied by rituals that enhance its significance, making the moment unforgettable. These rituals not only deepen the emotional impact of the gift but also create lasting memories for both the giver and the recipient.

- Engagement Proposals: In many cultures, the act of proposing with a ring is a deeply cherished ritual. It often involves a heartfelt speech, symbolizing the promise of a future together.

- Anniversary Celebrations: Gifting jewelry on anniversaries serves as a reminder of the time spent together. This ritual often includes a special dinner or event to commemorate the occasion.

- Family Heirlooms: Passing down jewelry through generations is a ritual that connects families. The stories behind these pieces often add layers of meaning, making them treasured gifts.

Rituals surrounding jewelry gifting are essential as they provide a framework for expressing emotions. They allow individuals to convey feelings that words may not adequately express. By participating in these rituals, givers and receivers create shared experiences that strengthen their bond.

Moreover, these rituals often reflect cultural heritage, showcasing the significance of jewelry in different societies. For instance, in some cultures, jewelry is not just a gift but a symbol of status and family lineage, making the act of giving even more meaningful.

Adding a personal touch to the jewelry gift can amplify the emotional experience. Customization options, such as engraving names or significant dates, make the piece unique and reflective of the relationship. This personalization transforms the jewelry into a one-of-a-kind treasure, symbolizing the unique bond shared between two individuals.

Furthermore, the way jewelry is presented can also enhance its emotional impact. Thoughtful packaging, accompanied by a heartfelt note, can elevate the entire experience, making the recipient feel cherished and valued.

The timing of the gift can significantly influence its emotional resonance. Special occasions such as birthdays, anniversaries, or significant life milestones are traditional times for giving jewelry. However, spontaneous gifts can also hold immense value, as they demonstrate thoughtfulness and affection without a specific reason.

For example, surprising a partner with a piece of jewelry on an ordinary day can create a memorable moment that stands out amidst the routine of everyday life. The element of surprise can make the gift even more impactful, reinforcing the idea that love and appreciation can be expressed at any time.

The memories created through the ritual of giving jewelry often last a lifetime. Each piece becomes a tangible reminder of a special moment, encapsulating the emotions and experiences associated with that time. Whether it’s a simple pendant received on a casual day or an elaborate engagement ring presented during a proposal, each piece tells a unique story.

As relationships evolve, these jewelry pieces can serve as milestones, marking the journey of love and commitment. They become cherished artifacts, often passed down to future generations, further deepening their significance within families.

In conclusion, the ritual of giving jewelry is more than just a tradition; it is a profound expression of love that encompasses emotions, cultural significance, and personal connections. By understanding and embracing these rituals, we can enhance our relationships and create lasting memories that resonate through time.

What Role Does Marketing Play in Jewelry as a Love Symbol?

The jewelry industry plays a pivotal role in shaping consumer perceptions of jewelry as the ultimate symbol of love. Through various marketing strategies, brands effectively communicate the emotional significance of jewelry, influencing how consumers view and purchase these treasured items.

Advertising campaigns are crucial in positioning jewelry as a representation of love and commitment. Many brands craft compelling narratives that resonate with consumers’ emotions, often featuring romantic stories that highlight the importance of gifting jewelry during significant life events. For instance, commercials showcasing proposals or anniversaries create a direct association between jewelry and love, making it a go-to gift for such occasions.

With the rise of social media, the jewelry industry has adapted its marketing strategies to leverage platforms like Instagram and Pinterest. These platforms allow brands to showcase their products visually and engage with a broader audience. Influencers and celebrities often play a significant role in promoting jewelry as symbols of love, sharing personal stories and experiences that connect with their followers. This organic promotion helps to normalize the idea of gifting jewelry as a token of affection, making it a popular choice among consumers.

Jewelry marketing often reflects cultural narratives that emphasize the significance of love and relationships. Different cultures have unique traditions surrounding jewelry, and marketers tap into these narratives to create relatable content. For instance, in many Western cultures, engagement rings are marketed as essential elements of proposals, reinforcing the idea that love is best expressed through such gifts. Similarly, in Eastern cultures, jewelry is often tied to rituals and ceremonies, which marketers highlight to appeal to consumers’ emotional connections.

Personalized jewelry has gained immense popularity, allowing consumers to express their unique love stories. Marketers emphasize the emotional value of customized pieces, such as engraved rings or birthstone necklaces, which can be tailored to reflect personal milestones or shared memories. This focus on personalization not only enhances the perceived value of the jewelry but also strengthens the emotional bond between the giver and receiver.

Pricing is another critical aspect of jewelry marketing. Brands often position their products at various price points to cater to different consumer segments. Luxury brands emphasize exclusivity and craftsmanship, appealing to those looking to make a significant statement of love. Conversely, more affordable brands promote accessibility, allowing a broader audience to partake in the tradition of gifting jewelry. This strategic pricing helps consumers feel that they can find the perfect piece that aligns with their budget while still conveying deep emotions.

As consumer preferences evolve, so do marketing strategies in the jewelry industry. Current trends include sustainability and ethical sourcing, which are becoming increasingly important to consumers. Brands that highlight their commitment to environmentally friendly practices and ethical labor conditions resonate with a growing demographic that values responsibility alongside romance. This shift not only attracts eco-conscious consumers but also reinforces the idea that love can be expressed through responsible choices.

In conclusion, the marketing strategies employed by the jewelry industry significantly influence consumer perceptions of jewelry as a symbol of love. Through advertising, social media engagement, cultural narratives, personalization, and pricing strategies, brands create a compelling case for why jewelry remains a cherished gift that embodies deep emotional connections.

Advertising Campaigns and Love

In the world of advertising, few themes resonate as profoundly as love and commitment. Many brands create compelling narratives around these emotions, particularly in the jewelry sector. This strategic approach not only highlights the beauty of the products but also shapes how consumers perceive jewelry as a gift, elevating it to a symbol of deep emotional connection.

Advertising campaigns are designed to tap into our emotions, making us feel a connection to the products being promoted. In the jewelry industry, this often involves storytelling that centers on romantic love, commitment, and celebration of significant life events. By portraying jewelry as an essential element of these moments, brands effectively position their products as more than mere accessories; they become symbols of affection and devotion.

Jewelry advertisements often employ various emotional triggers to engage consumers. These can include:

- Storytelling: Many campaigns tell a story that resonates with viewers, often depicting romantic proposals or anniversaries.

- Imagery: Beautiful visuals of couples sharing intimate moments while exchanging jewelry create a strong emotional appeal.

- Music: The right soundtrack can evoke feelings of nostalgia and warmth, enhancing the overall message of love.

Love stories are universally relatable and evoke strong emotional responses. By incorporating these narratives into their marketing strategies, jewelry brands can:

- Create a Connection: Consumers are more likely to connect with brands that understand their emotional needs.

- Encourage Sharing: Heartwarming stories often lead to social sharing, increasing brand visibility and reach.

- Foster Loyalty: When consumers feel an emotional bond with a brand, they are more likely to remain loyal customers.

Social media has revolutionized the way brands communicate with consumers. Jewelry brands leverage platforms like Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok to showcase their products in visually appealing ways. This has several benefits:

- Visual Storytelling: Social media allows brands to tell their stories through captivating images and videos, reaching a wider audience.

- User-Generated Content: Encouraging customers to share their own love stories and experiences with jewelry creates authentic connections.

- Influencer Collaborations: Partnering with influencers who align with the brand’s values can amplify the message of love and commitment.

Cultural context is crucial in shaping how jewelry is marketed. Different cultures have unique traditions and meanings associated with jewelry, which can influence advertising strategies. For example:

- Engagement and Wedding Traditions: In many Western cultures, diamond engagement rings symbolize commitment, while in Eastern cultures, gold jewelry is often preferred.

- Seasonal Campaigns: Brands may tailor their advertising to align with cultural events, like Valentine’s Day or Diwali, highlighting the significance of giving jewelry during these times.

With numerous brands vying for consumer attention, differentiation is key. Some strategies include:

- Personalization: Offering customizable jewelry options allows consumers to create unique gifts that reflect their personal stories.

- Ethical Sourcing: Highlighting the ethical sourcing of materials can appeal to socially conscious consumers.

- Innovative Designs: Unique and contemporary designs can attract younger audiences looking for something different.

In conclusion, the interplay between advertising and the emotional significance of jewelry plays a pivotal role in shaping consumer perceptions. By crafting compelling narratives around love and commitment, brands not only promote their products but also contribute to the cultural understanding of jewelry as a cherished gift.

Social Media Influence on Jewelry Trends

Social media platforms have transformed the way we perceive and interact with jewelry, particularly as a symbol of love. With millions of users sharing their personal stories, experiences, and styles, these platforms have become essential in shaping jewelry trends and influencing consumer choices.

Social media has become a powerful tool for jewelry designers and brands to showcase their creations. Through visually appealing posts and engaging content, they can reach a wider audience, capturing the attention of potential buyers. Platforms like Instagram and Pinterest are particularly effective, as they allow users to discover new styles and trends through images and videos.

Influencers have emerged as key players in the jewelry marketing landscape. By sharing their personal experiences with different jewelry pieces, they create a sense of authenticity and relatability. Their endorsements can significantly impact consumer behavior, leading to increased interest and sales for certain brands. This phenomenon is particularly evident in the promotion of engagement rings and personalized jewelry, where influencers often share their own love stories and the significance of their jewelry choices.

Yes, hashtags are crucial for discovering the latest jewelry trends on social media. By using popular hashtags like #JewelryOfTheDay or #EngagementRing, users can easily find inspiration and connect with others who share similar interests. This not only fosters a sense of community but also helps brands gain visibility among target audiences.

User-generated content, such as customer photos and reviews, plays a significant role in shaping consumer perceptions. When potential buyers see real people wearing and enjoying jewelry, it creates a sense of trust and encourages them to make a purchase. Positive reviews and testimonials can also enhance a brand’s reputation, making it more appealing to new customers.

- Minimalist Designs: Simple, elegant pieces that resonate with a modern audience.

- Personalization: Customized jewelry that reflects individual stories and emotions.

- Sustainable Choices: Eco-friendly jewelry options that appeal to environmentally-conscious consumers.

Absolutely. Social media allows users to share their personal stories related to jewelry, such as engagements, anniversaries, and other milestones. This sharing fosters emotional connections, making jewelry not just a physical item but a representation of significant life events and feelings. The visual storytelling that unfolds on these platforms enhances the emotional weight that jewelry carries as a symbol of love.

The influence of social media on consumer behavior cannot be overstated. As users scroll through their feeds, they are exposed to a constant stream of jewelry inspiration, which can lead to impulsive buying decisions. The ability to see how jewelry looks on different people and in various settings makes it easier for consumers to envision themselves wearing similar pieces, ultimately driving sales.

Brands must be strategic in their approach to social media marketing. Understanding their target audience and creating content that resonates with them is essential. Engaging visuals, authentic storytelling, and interactive elements can help brands build a loyal following and encourage user participation. Additionally, collaborating with influencers who align with their brand values can amplify their reach and credibility.

In conclusion, social media has revolutionized the jewelry industry, impacting how people perceive and choose jewelry as symbols of love. By leveraging these platforms effectively, brands can connect with consumers on a deeper level, making jewelry not just a gift, but a cherished representation of love and commitment.

How to Choose the Perfect Jewelry Gift?

Choosing the perfect jewelry gift can be a delightful yet daunting task. Jewelry is not merely an accessory; it is a symbol of love, commitment, and personal expression. To ensure that your gift resonates deeply with the recipient, consider the following factors:

Understanding your partner’s style is crucial. Different individuals have unique tastes when it comes to jewelry. Some may prefer classic designs, while others lean towards modern or eclectic pieces. Observing what your partner typically wears can provide valuable insights. Consider the following:

- Metal Preference: Does your partner prefer gold, silver, or platinum?

- Gemstone Choices: Are they drawn to diamonds, sapphires, or perhaps more unconventional stones like opals?

- Style: Do they favor minimalist designs or intricate, ornate pieces?

The occasion for gifting jewelry can significantly influence your selection. Different events may call for different types of jewelry:

- Anniversaries: Consider personalized pieces, such as engraved bracelets or custom-made rings.

- Birthdays: A birthstone necklace can add a personal touch, celebrating their unique identity.

- Graduations: Elegant earrings or a sophisticated watch can symbolize their achievement and new beginnings.

Jewelry can convey powerful messages. Are you expressing love, friendship, or appreciation? The type of jewelry you choose can reflect this:

- Romantic Messages: An engagement ring or a heart-shaped pendant signifies deep love and commitment.

- Friendship: Matching bracelets can symbolize a strong bond and shared experiences.

- Appreciation: A thoughtful piece can express gratitude, such as a locket containing a cherished photo.

Setting a budget is essential when choosing jewelry. It helps narrow down options while ensuring that you select a piece that feels meaningful. Consider the following:

- Quality vs. Cost: Higher-quality materials may come at a premium, but they often last longer and carry more sentimental value.

- Customization: Custom pieces may require a larger budget, but they can be worth the investment for their uniqueness.

- Sales and Discounts: Keep an eye out for seasonal sales or promotions to get the best value.

When it comes to purchasing jewelry, you have several options:

- Local Jewelers: Visiting a local jeweler allows you to see and feel the pieces before buying.

- Online Retailers: Online shopping offers a vast selection, often with customer reviews to guide your choice.

- Custom Designers: If you’re looking for something unique, consider working with a designer to create a custom piece.

In conclusion, selecting the perfect jewelry gift requires a thoughtful approach that considers personal preferences, the occasion, and the message you wish to convey. By taking the time to understand these elements, you can choose a piece that will be cherished for years to come.

Understanding Your Partner’s Style

When it comes to selecting the perfect piece of jewelry for your partner, understanding their unique style is of utmost importance. This process not only ensures that the gift resonates with them but also makes the act of giving feel deeply personal and meaningful. By taking the time to learn about your partner’s preferences, you can choose jewelry that reflects their individuality and enhances their natural beauty.

Jewelry is more than just an accessory; it serves as a reflection of personal identity. Knowing what your partner loves can help you select a piece that resonates with their personality, making the gift more special. Here are some reasons why understanding their taste is crucial:

- Personal Connection: A thoughtful gift shows that you care and have put effort into understanding their likes and dislikes.

- Enhanced Emotional Value: Jewelry that aligns with their style is likely to be cherished more, as it feels like a true representation of their essence.

- Avoiding Missteps: Knowing their preferences can help you avoid gifts that may not suit them, ensuring your gesture is well-received.

Understanding your partner’s taste in jewelry can be a fun and engaging process. Here are some practical tips to guide you:

- Observe Their Current Jewelry: Pay attention to the pieces they frequently wear. Do they prefer gold or silver? Are their choices more classic or contemporary?

- Ask Indirect Questions: Casually inquire about their favorite gemstones or styles during conversations. This can provide valuable insights without revealing your intentions.

- Involve Them in the Process: If appropriate, consider shopping together. This not only helps you gauge their preferences but also makes for a fun date.

Understanding your partner’s personality can also guide you in selecting the right jewelry. Here are some styles that resonate with various personality types:

| Personality Type | Jewelry Style |

|---|---|

| Classic | Timeless pieces like diamond studs or simple gold necklaces. |

| Trendy | Bold, statement pieces that reflect current fashion trends. |

| Artistic | Unique, handcrafted jewelry that showcases creativity. |

| Minimalist | Sleek and simple designs that emphasize elegance without excess. |

To make your gift even more special, consider personalizing it. Here are some ideas:

- Engravings: Adding a meaningful date or a short message can enhance the sentimental value of the piece.

- Custom Designs: Collaborate with a jeweler to create a one-of-a-kind piece that embodies your partner’s taste.

- Choosing Birthstones: Incorporating their birthstone can add a personal touch that signifies your love and connection.

In conclusion, understanding your partner’s style is essential when selecting jewelry that speaks to them. By paying attention to their preferences, observing their current jewelry, and considering their personality, you can choose a piece that they will cherish for years to come. Remember, a thoughtful gift not only enhances your relationship but also serves as a beautiful reminder of your love.

Budgeting for Jewelry Purchases

When it comes to selecting the perfect piece of jewelry, budgeting plays a crucial role in the decision-making process. A well-defined budget not only helps in narrowing down choices but also ensures that the gift remains thoughtful and heartfelt, symbolizing your love in a meaningful way. But how do you effectively set a budget for jewelry purchases?

Setting a budget is essential for several reasons:

- Limits Choices: A clear budget helps to focus on options that are financially feasible, reducing the overwhelming number of choices available.

- Prevents Overspending: By establishing a budget, you can avoid the temptation of splurging on extravagant pieces that may not align with your financial situation.

- Encourages Thoughtfulness: When you work within a budget, you are more likely to consider the recipient’s preferences and the meaning behind the gift, ensuring it resonates emotionally.

Determining a budget for jewelry can be straightforward if you follow a few simple steps:

- Assess Your Finances: Take a close look at your current financial situation. Consider your income, savings, and any upcoming expenses.

- Define the Occasion: The significance of the occasion can influence your budget. For instance, an engagement ring may warrant a higher budget compared to a birthday gift.

- Research Market Prices: Familiarize yourself with the price ranges for different types of jewelry. This can help you set a realistic budget based on what you can afford.

Sticking to your budget provides several advantages:

- Reduces Stress: Knowing your spending limits can alleviate the anxiety that often accompanies gift shopping.

- Enhances Satisfaction: Choosing a well-thought-out piece within your budget can lead to greater satisfaction for both the giver and the recipient.

- Fosters Creativity: Working within a budget can inspire creative thinking, leading to unique gift ideas that may not have been considered otherwise.

Here are some practical tips to help you find a meaningful piece of jewelry without breaking the bank:

- Consider Alternative Materials: Instead of traditional gold or diamonds, explore options like silver, gemstones, or lab-created diamonds, which can be more affordable.

- Look for Sales and Discounts: Keep an eye out for seasonal sales or special promotions, which can provide significant savings on jewelry purchases.

- Personalized Options: Customizing a piece of jewelry can add sentimental value without necessarily increasing the cost. Engraving a special date or message can make a simple piece feel unique.

Ultimately, setting a budget for jewelry purchases is about making informed choices that reflect your emotions and intentions. By being mindful of your finances while considering the recipient’s preferences, you can find a piece that truly symbolizes your love without compromising on thoughtfulness or significance.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why is jewelry considered a symbol of love?

Jewelry has long been associated with love due to its beauty and ability to convey deep emotions. It serves as a tangible reminder of special moments and commitments, making it a cherished gift across cultures.

- What types of jewelry are most commonly given as gifts?

Common gifts include engagement rings, necklaces, bracelets, and earrings. Each piece can carry personal significance, reflecting the giver’s feelings and the recipient’s style.

- How do cultural differences influence jewelry gifting?

Cultural traditions play a significant role in how jewelry is perceived and given. For example, in Western cultures, engagement rings symbolize commitment, while in Eastern cultures, jewelry often has ties to rituals and heritage.

- What is the importance of personalized jewelry?

Personalized jewelry adds a unique touch, allowing the giver to express their emotions in a special way. Engravings or custom designs make the piece even more memorable and meaningful.

- How can I choose the right jewelry for my partner?

Understanding your partner’s style and preferences is key. Consider their favorite metals, gemstones, and the occasions that matter to them, which will help you select a piece that resonates with their personality.