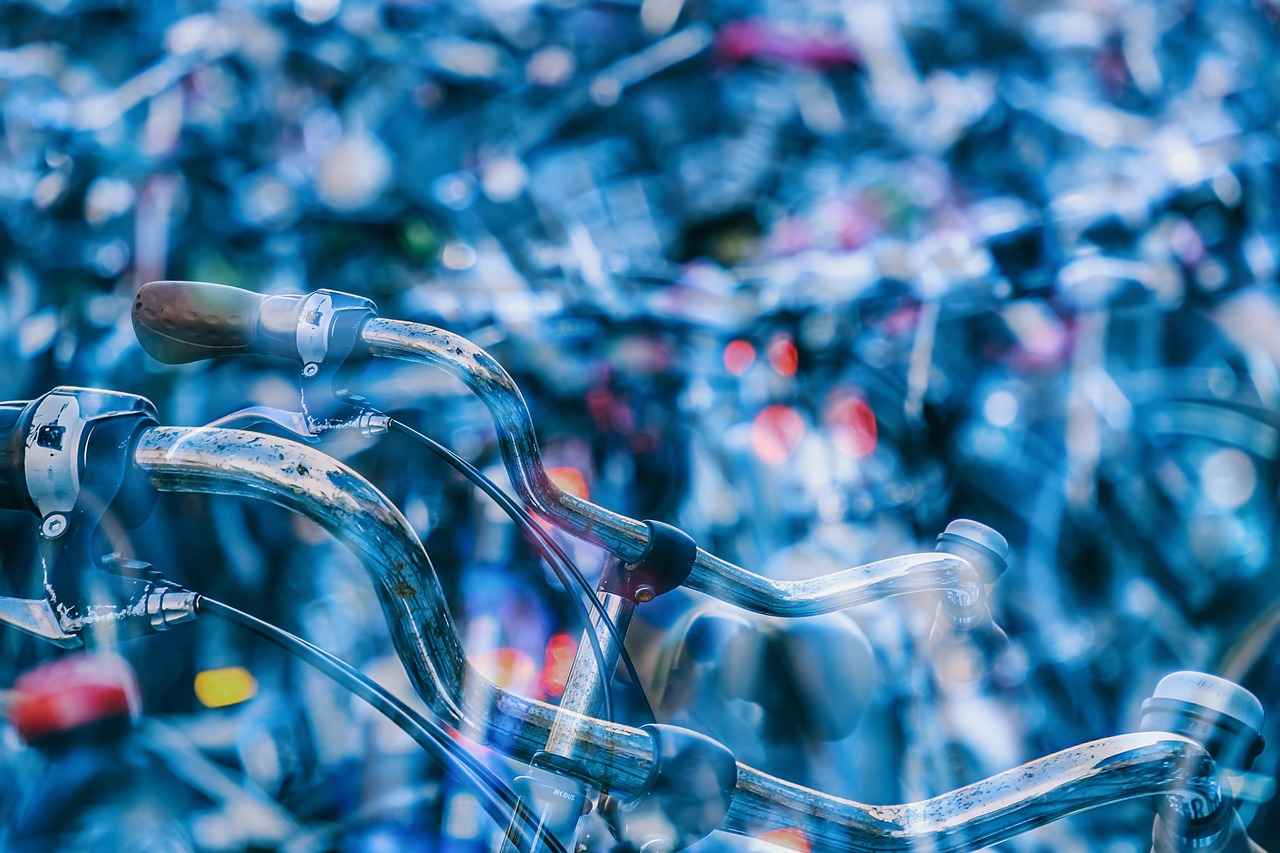

Electric bikes, or e-bikes, are revolutionizing the way we commute and enjoy recreational rides. With advancements in technology and design, these bikes offer a perfect blend of convenience, sustainability, and fun. This comprehensive guide will delve into the latest models transforming urban commuting and recreational riding, focusing on their features, performance, and user experiences to help you choose the ideal e-bike for your lifestyle.

1. The Rise of Electric Bikes

The popularity of electric bikes has skyrocketed in recent years. Factors such as increased urbanization, environmental concerns, and the need for efficient transportation have contributed to this trend. E-bikes provide an eco-friendly alternative to traditional vehicles, allowing riders to navigate city streets with ease while reducing their carbon footprint.

2. Key Features to Look for in an E-Bike

When selecting an electric bike, understanding essential features is crucial. Key considerations include:

- Battery Life and Range: Evaluate the bike’s battery capacity to ensure it meets your commuting or recreational needs.

- Motor Power: The motor type affects speed and hill-climbing capabilities.

- Frame Design: A lightweight yet durable frame enhances performance and comfort.

3. Top Electric Bike Models of 2023

This year brings an exciting array of e-bike models, each with unique features:

- Model A: The Commuter’s Choice, renowned for its lightweight frame and exceptional battery life.

- Model B: The Off-Road Beast, designed for adventure enthusiasts seeking rugged performance.

4. User Experiences and Reviews

Real user feedback is invaluable. Many riders appreciate the convenience and efficiency of e-bikes, while others voice common complaints. Understanding both perspectives can guide potential buyers in their decision-making process.

5. Maintenance Tips for Electric Bikes

Proper maintenance is essential for longevity. Regular checks on battery health, tire pressure, and brake functionality can keep your e-bike in top condition.

6. The Future of Electric Bikes

As technology evolves, so do electric bikes. Upcoming trends include enhanced battery technologies, smart connectivity features, and improved safety measures, promising an exciting future for e-biking.

7. Conclusion: Making the Right Choice

Choosing the right electric bike involves careful consideration of features, user reviews, and personal needs. By evaluating these aspects, you can make an informed decision that enhances your riding experience.

1. The Rise of Electric Bikes

Electric bikes have become a significant part of modern transportation, experiencing a remarkable surge in popularity over recent years. This increase can be attributed to several key factors that align with the growing demand for sustainable and efficient commuting options.

One of the primary drivers behind this trend is the increasing awareness of environmental issues. As urban areas become more congested and pollution levels rise, many individuals are seeking eco-friendly alternatives to traditional vehicles. Electric bikes provide a solution by producing zero emissions during operation, making them an attractive option for environmentally conscious consumers.

Additionally, advancements in technology have greatly improved the performance and affordability of electric bikes. Modern e-bikes are equipped with powerful batteries that offer extended ranges, allowing riders to travel longer distances without the need for frequent recharging. This has made them a viable option for daily commutes, recreational riding, and even long-distance travel.

Furthermore, the health benefits of riding an electric bike cannot be overlooked. While they provide assistance, riders still engage in physical activity, promoting cardiovascular health and overall fitness. This combination of exercise and convenience appeals to a wide range of individuals, from casual riders to fitness enthusiasts.

Another factor contributing to the rise of electric bikes is the increasing availability of various models designed to meet diverse needs. From commuter bikes to off-road models, there is an e-bike for everyone. This variety encourages more people to consider electric bikes as a practical transportation solution.

In conclusion, the rise of electric bikes can be attributed to their eco-friendliness, technological advancements, health benefits, and the wide range of available models. As more individuals recognize these advantages, the popularity of electric bikes is likely to continue growing, transforming the way we think about personal transportation.

2. Key Features to Look for in an E-Bike

When it comes to selecting the perfect electric bike, understanding the key features is essential to ensure it meets your specific needs. This section delves into the most important aspects to consider, including battery life, motor power, and frame design.

Battery Life and Range

The battery is one of the most critical components of an electric bike. It not only determines how far you can travel on a single charge but also influences the overall performance of the bike. Look for bikes with a battery capacity that aligns with your typical riding distances. A good rule of thumb is to aim for a range that exceeds your daily commute to avoid running out of power unexpectedly.

- Consider the type of battery: Lithium-ion batteries are popular for their longevity and efficiency.

- Charging times: Some batteries take longer to charge than others, which can affect your riding schedule.

Motor Power and Performance

The motor is essentially the heart of the electric bike, providing the necessary power to assist your pedaling. When evaluating motors, consider the wattage; higher wattage typically translates to better performance, especially on inclines. Additionally, check if the motor is hub-mounted or mid-drive, as each offers different riding experiences.

- Hub motors: Generally simpler and quieter, ideal for city commuting.

- Mid-drive motors: Offer better weight distribution and performance on varied terrains.

Frame Design and Comfort

The frame design of an electric bike can significantly impact your comfort and riding experience. Look for a frame that suits your riding style, whether it’s a step-through design for easy mounting or a more traditional sporty frame. Additionally, consider the bike’s weight and materials, as these factors affect maneuverability and durability.

In summary, selecting an electric bike requires careful consideration of these key features. By paying attention to battery life, motor power, and frame design, you can find a bike that perfectly aligns with your riding needs and enhances your overall experience.

2.1 Battery Life and Range

Battery Life and RangeThe battery capacity of an electric bike (e-bike) plays a crucial role in determining its overall range and usability. Understanding how to evaluate battery specifications is essential for anyone considering an e-bike, whether for daily commuting or leisurely rides. In this section, we will delve into the factors that influence battery performance and how they can meet your specific needs.

Understanding Battery Capacity

Battery capacity is measured in ampere-hours (Ah) or watt-hours (Wh), which indicates how much energy the battery can store. A higher capacity typically translates to a longer range. For example, a bike with a 500Wh battery can generally travel further than one with a 300Wh battery, assuming other factors like weight and terrain are constant.

Evaluating Your Needs

When assessing battery specifications, consider your typical riding distance. If you plan to use your e-bike for daily commutes of 20 miles or more, opt for a battery with a higher capacity. Conversely, for short rides or errands, a smaller battery may suffice.

Factors Affecting Range

- Terrain: Hilly areas require more power, reducing the range.

- Rider Weight: Heavier riders may experience shorter ranges.

- Assist Level: Higher pedal-assist settings consume more battery.

Battery Maintenance Tips

To maximize your e-bike’s range, proper battery maintenance is essential. Here are some tips:

- Charge regularly and avoid letting the battery drain completely.

- Store the battery in a cool, dry place.

- Follow the manufacturer’s guidelines for charging and usage.

In conclusion, understanding battery life and range is fundamental when selecting an e-bike. By evaluating your needs and considering the factors that influence battery performance, you can ensure your e-bike meets your commuting or recreational demands.

2.1.1 Types of Batteries

When it comes to electric bikes, the choice of battery type plays a critical role in determining both performance and longevity. Understanding the different battery technologies available can help riders make informed decisions that align with their riding habits and preferences. Below, we explore the most common types of batteries used in electric bikes, along with their respective advantages and disadvantages.

| Battery Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium-Ion (Li-ion) |

|

|

| Lead-Acid |

|

|

| Nickel-Metal Hydride (NiMH) |

|

|

In summary, lithium-ion batteries are the most popular choice for electric bikes due to their superior energy density and longevity, making them ideal for daily commuters. On the other hand, lead-acid batteries may appeal to those on a budget but come with significant weight and lifespan drawbacks. Nickel-metal hydride batteries offer a middle ground but may not be as efficient as lithium-ion options.

Ultimately, the choice of battery type depends on individual needs, riding conditions, and budget considerations. Riders should weigh the pros and cons of each battery type to choose the best fit for their electric biking experience.

2.1.2 Charging Times

Charging times are a crucial aspect of owning an electric bike, as they can significantly influence your riding schedule and overall experience. Understanding how long it takes to charge your e-bike can help you plan your rides more effectively and ensure that you never find yourself stranded with a depleted battery.

Typically, the charging duration for e-bike batteries can vary based on several factors, including battery capacity, charger type, and the state of the battery when you start charging. Most e-bike batteries take between 3 to 6 hours to fully charge. However, some advanced models with fast-charging capabilities can reduce this time to as little as 1 to 2 hours.

To optimize your e-bike’s battery life and charging efficiency, consider the following tips:

- Use the Right Charger: Always use the charger that comes with your e-bike or one recommended by the manufacturer. Using the wrong charger can lead to longer charging times or even damage the battery.

- Avoid Overcharging: Most modern e-bikes are equipped with smart charging technology that prevents overcharging. However, it’s still good practice to unplug the charger once the battery is fully charged.

- Charge Regularly: Keeping your battery charged between 20% and 80% can prolong its lifespan. Avoid letting it drop to 0% frequently, as this can degrade the battery over time.

- Temperature Matters: Charge your e-bike in a moderate temperature range. Extreme heat or cold can affect charging efficiency and battery performance.

In conclusion, being aware of your e-bike’s charging times and following best practices can enhance your riding experience. Planning your rides around charging schedules ensures that your bike is always ready when you are, allowing you to enjoy the freedom and convenience that electric biking offers.

2.2 Motor Power and Performance

The motor is undeniably the heart of an electric bike, playing a crucial role in determining its overall performance. Understanding the various types of motors available can significantly influence your riding experience, particularly in terms of speed and hill-climbing ability.

Electric bike motors can generally be categorized into three main types: hub motors, mid-drive motors, and gearless motors. Each type has its unique characteristics and applications, which can greatly affect how the bike performs under different conditions.

| Motor Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Hub Motors | Quiet operation, low maintenance, and easy installation. | Limited hill-climbing ability and can be less efficient on steep inclines. |

| Mid-Drive Motors | Better weight distribution, superior hill-climbing capability, and efficient energy use. | More complex to maintain and can wear down the bike’s chain and gears. |

| Gearless Motors | Highly reliable, low maintenance, and excellent for urban commuting. | Less torque compared to geared motors, which may affect acceleration. |

When considering motor power, it’s essential to look at the wattage of the motor. Higher wattage typically translates to more power, which can enhance speed and climbing ability. For instance, a motor rated at 750 watts will generally provide a more robust performance compared to one rated at 250 watts.

Moreover, the placement of the motor also matters. Mid-drive motors tend to offer better torque for climbing steep hills, making them ideal for mountainous terrains. In contrast, hub motors are often more suited for flat urban environments.

Ultimately, the choice of motor will depend on your specific riding needs. Whether you prioritize speed for commuting or power for off-road adventures, understanding the differences in motor types and their impact on performance will help you make an informed decision.

3. Top Electric Bike Models of 2023

This section provides an in-depth look at the top electric bike models available in 2023. Each model is evaluated based on its unique features, performance metrics, and overall user satisfaction. With the growing demand for electric bikes, it’s essential to understand what sets these models apart in a competitive market.

- Model A: The Commuter’s Choice

- Lightweight Design: Weighing in at just 40 pounds, this bike is perfect for navigating busy urban environments.

- Impressive Battery Life: With a range of up to 60 miles on a single charge, commuters can travel further without the need for frequent recharging.

- Integrated Technology: Features like Bluetooth connectivity and a built-in GPS make this model a favorite among tech-savvy riders.

- Model B: The Off-Road Beast

- Robust Build: Designed to withstand rugged terrains, this bike features a durable frame and high-quality suspension system.

- Powerful Motor: Equipped with a 750W motor, it can tackle steep hills and rough paths with ease.

- User Feedback: Riders rave about its stability and performance, especially in challenging environments.

- Model C: The Versatile All-Rounder

- Hybrid Features: This model combines the best of both worlds, suitable for both city riding and light off-road adventures.

- Customizable Options: Riders can choose from various accessories, including racks and fenders, to tailor the bike to their needs.

- Positive Reviews: Users appreciate its adaptability and comfort during long rides.

As electric bikes continue to evolve, these models represent the forefront of innovation and user satisfaction in 2023. Riders should consider their specific needs and preferences when choosing the right e-bike, ensuring they select a model that enhances their riding experience.

3.1 Model A: The Commuter’s Choice

Model A has quickly become a top choice for urban commuters, revolutionizing the way people navigate city streets. With its lightweight frame and robust battery life, this electric bike is engineered to meet the demands of daily city riding. Riders appreciate its agility and ease of handling, making it perfect for weaving through traffic and maneuvering tight spaces.

One of the standout features of Model A is its impressive battery capacity. Designed for efficiency, it offers a range that allows riders to cover significant distances without the need for frequent recharging. This is particularly beneficial for those who rely on their bike for commuting to work or running errands. With a typical range of up to 50 miles on a single charge, Model A ensures that you can confidently tackle your daily journeys.

In addition to its performance, Model A boasts a sleek and modern design that appeals to a wide range of riders. The ergonomic seating and adjustable handlebars provide comfort during longer rides, while the integrated lights and reflectors enhance safety during nighttime commutes. Furthermore, Model A’s puncture-resistant tires add an extra layer of reliability, ensuring that you can ride with peace of mind.

Many users have shared their positive experiences with Model A, highlighting its ease of use and low maintenance requirements. The bike’s intuitive controls and user-friendly interface make it accessible for riders of all skill levels. Additionally, the lightweight design makes it easy to carry up stairs or onto public transportation, further enhancing its appeal for city dwellers.

In conclusion, Model A is not just an electric bike; it’s a game-changer for urban commuting. With its combination of performance, style, and convenience, it has earned its place as a favorite among city riders. Whether you’re commuting to work or exploring the city, Model A delivers a seamless and enjoyable riding experience.

3.2 Model B: The Off-Road Beast

For adventure enthusiasts seeking a thrilling experience on rugged terrains, Model B stands out as a top choice. This electric bike is engineered to tackle challenging landscapes, offering a perfect blend of durability and performance.

One of the most remarkable features of Model B is its rugged design. Built with high-quality materials, it can withstand the toughest conditions, making it ideal for off-road adventures. The bike’s reinforced frame and heavy-duty tires provide exceptional stability and traction, allowing riders to conquer steep hills and uneven surfaces with ease.

Performance-wise, Model B is equipped with a powerful motor that delivers impressive torque, enabling it to ascend inclines effortlessly. Riders have reported a smooth and exhilarating ride, even on the most challenging trails. The bike’s advanced suspension system absorbs shocks, enhancing comfort during long rides over bumpy terrain.

Battery life is another critical aspect of Model B. The bike is fitted with a high-capacity battery that offers an extensive range, ensuring that adventure seekers can explore without worrying about running out of power. Users have praised the bike for its reliable performance and the ability to tackle long-distance rides without frequent recharging.

User feedback highlights the versatility of Model B. Many riders appreciate its ability to transition seamlessly between off-road and urban environments, making it a perfect companion for weekend adventures or daily commutes. The bike’s user-friendly controls and customizable settings allow riders to tailor their experience to their preferences.

In conclusion, Model B is not just an electric bike; it’s a gateway to adventure. With its rugged design, powerful performance, and positive user feedback, it is an exceptional choice for those looking to explore the great outdoors.

4. User Experiences and Reviews

User Experiences and Reviews

When it comes to choosing an electric bike, real user reviews serve as a crucial resource for potential buyers. These testimonials provide invaluable insights into the performance, reliability, and overall satisfaction of various electric bike models. By compiling feedback from riders, we aim to present a comprehensive overview that captures the essence of user experiences.

4.1 Positive Reviews

Many riders express their enthusiasm for electric bikes, highlighting several key benefits:

- Convenience: The ease of use and accessibility of electric bikes make them a popular choice for daily commuting.

- Efficiency: Users appreciate the energy savings and reduced travel time, especially in urban environments.

- Eco-Friendliness: Riders often mention the positive environmental impact of opting for electric bikes over traditional vehicles.

For instance, one user noted, “Switching to an electric bike has transformed my commute. I no longer sit in traffic and can park easily!”

4.2 Common Complaints

While the majority of feedback is positive, some riders have voiced concerns:

- Battery Life: Some users report that battery performance does not meet their expectations, especially on longer rides.

- Weight: A few riders find certain models heavier than anticipated, making them difficult to transport.

- Cost: The initial investment can be a barrier for some potential buyers, as high-quality electric bikes tend to be more expensive.

One user remarked, “I love my e-bike, but I wish the battery lasted longer during my weekend rides.”

Conclusion

In summary, user reviews offer a well-rounded perspective on electric bikes, revealing both the strengths and weaknesses of various models. By considering these insights, potential buyers can make informed decisions that align with their riding needs and preferences.

4.1 Positive Reviews

Positive Reviews of Electric Bikes

Electric bikes have garnered a significant amount of positive feedback from users around the globe. As more individuals embrace this innovative mode of transportation, many riders share their experiences, highlighting the numerous advantages of e-bikes. Below, we explore the most common positive experiences shared by riders, showcasing why electric bikes are becoming a preferred choice for many.

- Convenience: One of the most frequently mentioned benefits is the convenience electric bikes offer. Riders appreciate the ease of commuting without the hassle of traffic jams or parking difficulties. Many users find that e-bikes allow them to navigate urban environments quickly and efficiently.

- Efficiency: Electric bikes provide an efficient means of transportation, enabling riders to travel longer distances without exerting excessive effort. This is particularly beneficial for those who may not be in peak physical condition or for individuals looking to commute without arriving at their destination exhausted.

- Eco-Friendly: Users often express satisfaction with the environmental benefits of electric bikes. By choosing an e-bike over a car, riders contribute to reducing carbon emissions and promoting sustainable transportation options.

- Cost-Effective: Many riders find that, despite the initial investment, electric bikes prove to be cost-effective in the long run. Savings on fuel, parking fees, and public transport costs can add up significantly over time.

- Health Benefits: While e-bikes provide assistance, they still encourage physical activity. Users appreciate that they can enjoy the outdoors and maintain an active lifestyle without the strain of traditional cycling.

Overall, the positive reviews from electric bike users highlight a transformational shift in how people view commuting and recreational biking. With their blend of convenience, efficiency, and eco-friendliness, electric bikes are not just a trend; they are a viable solution for modern transportation challenges.

4.2 Common Complaints

While electric bikes have gained immense popularity for their convenience and eco-friendliness, they are not without their challenges. Understanding the common complaints can help potential buyers make informed decisions before investing in an e-bike.

- Battery Issues: One of the most frequent concerns among e-bike users is related to battery life. Many riders report that batteries do not hold a charge as expected, leading to shorter rides than anticipated. It’s crucial for potential buyers to consider the battery capacity and the brand reputation before making a purchase.

- Weight: E-bikes tend to be heavier than traditional bicycles due to the added components like the motor and battery. Some users find this cumbersome, especially when they need to lift the bike or transport it. Buyers should check the weight specifications and consider their own physical capabilities.

- Cost: The initial investment for an e-bike can be significant. Many riders express concern over the high price point, which can deter potential buyers. It’s important to weigh the long-term savings on transportation against the upfront cost.

- Maintenance Challenges: Like any vehicle, e-bikes require maintenance, and some users feel that the upkeep can be more complicated than with traditional bikes. This includes potential repairs for the electrical components, which can be costly. Buyers should seek models with accessible service options.

- Limited Range: Depending on the model, some e-bikes may have a limited range, which can be a dealbreaker for those who plan to use them for long commutes. It’s advisable to assess the range capabilities and ensure they meet personal commuting needs.

In conclusion, while e-bikes offer numerous benefits, being aware of these common complaints can help prospective buyers make a more informed choice. By considering factors such as battery life, weight, cost, maintenance, and range, individuals can find an electric bike that best suits their lifestyle and needs.

5. Maintenance Tips for Electric Bikes

Proper maintenance is essential for the longevity and performance of your electric bike. By following a few simple yet effective care tips, you can ensure that your e-bike remains in top condition for years to come. Here are some practical suggestions to keep your ride smooth and reliable:

- Regular Cleaning: Keeping your e-bike clean is crucial. Use a damp cloth to wipe down the frame and components, and avoid using a high-pressure hose, as it can damage electrical parts. Make it a habit to clean your bike after every few rides, especially if you’ve been on muddy trails.

- Battery Care: The battery is one of the most important components of your electric bike. Always follow the manufacturer’s guidelines for charging and storage. Avoid letting the battery completely discharge, and store it in a cool, dry place when not in use.

- Tire Maintenance: Check your tire pressure regularly, as under-inflated tires can affect performance and safety. Inspect the tires for any signs of wear and replace them if necessary. Maintaining proper tire pressure will enhance your bike’s efficiency and comfort.

- Brake Inspection: Regularly check your brakes to ensure they are functioning correctly. Look for any signs of wear on brake pads and make adjustments as needed. Effective brakes are crucial for your safety, especially when riding in varying terrains.

- Chain Lubrication: Keep your bike’s chain well-lubricated to prevent rust and ensure smooth shifting. Use a suitable lubricant and wipe off any excess to avoid attracting dirt. A well-maintained chain can significantly enhance your bike’s performance.

Conclusion: By incorporating these maintenance tips into your routine, you can prolong the life of your electric bike and improve its performance. Regular care not only enhances your riding experience but also ensures that your investment remains valuable over time. Remember, a well-maintained e-bike is a reliable companion for all your adventures!

6. The Future of Electric Bikes

The Future of Electric Bikes is an exciting topic as advancements in technology continue to reshape the landscape of personal transportation. With the rise of urbanization and environmental concerns, electric bikes (e-bikes) are poised to play a crucial role in sustainable commuting solutions.

As we look ahead, several key trends and innovations are expected to influence the future of e-biking:

- Smart Technology Integration: E-bikes are becoming increasingly integrated with smart technology. Features such as GPS navigation, fitness tracking, and mobile app connectivity will enhance the riding experience. Users will be able to monitor their performance, battery status, and even locate their bike if lost.

- Improved Battery Technology: Innovations in battery technology are crucial for the future of e-bikes. We can expect to see lighter, more efficient batteries that offer longer ranges and faster charging times. Solid-state batteries, for example, promise to revolutionize energy storage, providing higher energy density and safety.

- Enhanced Safety Features: Safety is paramount for e-bike riders. Future models may include advanced braking systems, built-in lights, and collision detection technology. These features will help reduce accidents and improve overall rider confidence.

- Customization and Personalization: As e-bikes become more popular, manufacturers will likely offer more customization options. Riders will be able to personalize their bikes with different colors, accessories, and tech features to match their style and preferences.

- Eco-Friendly Materials: Sustainability will remain a key focus in the manufacturing of e-bikes. Future models may utilize recycled materials and environmentally friendly production processes, further appealing to eco-conscious consumers.

In conclusion, the future of electric bikes looks promising, with innovations that enhance performance, safety, and user experience. As technology continues to evolve, e-bikes will undoubtedly become a more integral part of our daily lives, offering a sustainable and efficient alternative to traditional transportation methods.

7. Conclusion: Making the Right Choice

In the ever-evolving world of electric bikes, making an informed choice is essential for maximizing your riding experience. With various models flooding the market, it’s crucial to focus on specific features that cater to your needs. When selecting an electric bike, consider factors such as battery life, motor power, and the overall design.

Start by evaluating the battery life and range of the bike. A longer battery life ensures that you can travel greater distances without the need for frequent recharging. Additionally, understanding the types of batteries used in e-bikes can help you gauge their performance and longevity. Some batteries may charge faster but have a shorter lifespan, while others may take longer to charge but offer extended usage.

Motor power is another critical aspect to consider. The strength of the motor directly affects your bike’s speed and ability to handle inclines. Riders who frequently navigate hilly terrain should prioritize models with more powerful motors to enhance their riding experience. Furthermore, user feedback can provide invaluable insights into the real-world performance of different models, highlighting both strengths and weaknesses.

Moreover, take into account the frame design and overall build quality. A lightweight yet sturdy frame can significantly improve your riding comfort and maneuverability. Look for reviews that discuss the bike’s handling and stability, as these factors can greatly influence your satisfaction with the purchase.

In summary, selecting the right electric bike requires a careful analysis of various features and user experiences. By focusing on battery life, motor power, and frame design, you can make a well-informed decision that aligns with your riding style and needs. Always remember to consult user reviews and expert insights to ensure that your chosen model is the best fit for you.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What are the main benefits of riding an electric bike?

Electric bikes offer numerous advantages, including eco-friendliness, cost savings on fuel, and the ability to navigate urban traffic easily. They provide a fun and efficient way to commute or explore, making cycling accessible to a broader audience.

- How do I choose the right electric bike for my needs?

When selecting an electric bike, consider factors like battery life, motor power, and frame design. Think about how you plan to use it—whether for commuting, leisure, or off-road adventures—and pick a model that meets those specific needs.

- What is the typical charging time for electric bike batteries?

Charging times can vary based on the battery type and capacity, but most e-bikes take between 4 to 6 hours to fully charge. Some fast chargers can reduce this time significantly, allowing you to get back on the road quicker!

- Are electric bikes suitable for all terrains?

While many electric bikes are designed for urban commuting, there are models specifically built for off-road use. If you plan to tackle rough terrains, look for bikes with rugged tires and powerful motors to ensure a smooth ride.

- How can I maintain my electric bike?

Regular maintenance is key to keeping your electric bike in top shape. This includes checking tire pressure, cleaning the chain, and ensuring the battery is charged properly. Following the manufacturer’s guidelines will help prolong your bike’s life.